Credible authors & Academics

Sæmundur ”Fróði” Sigfússon

Sæmundr Sigfússon, better known as Sæmundr fróði (Sæmundr the Learned; 1056–1133), was an Icelandic priest and scholar.

Sæmundr is known to have studied abroad. Previously it has generally been held that he studied in France, but modern scholars rather believe his studies were carried out in Franconia. In Iceland he founded a long-lived school at Oddi. He was a member of the Oddaverjar clan and was the father of Loftur Sæmundsson.

Sæmundr wrote a work, probably in Latin, on the history of Norwegian kings. The work is now lost but was used as a source by later authors, including Snorri Sturluson. The poem Nóregs konungatal summarizes Sæmundr's work. The authorship of the Poetic Edda, or, more plausibly, just the editor's role in the compilation, was traditionally attributed to Sæmundr - Bishop Brynjulf asked in 1641 "Where now are those huge treasuries of all human knowledge written by Saemund the Wise, and above all that most noble Edda"? - but is not accepted today. It has been demonstrated by Svend Ellehøj that Sæmundr wrote in Latin a work that influenced highly on Nóregs konungatal, and the Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason by Oddr Snorrason.

In Icelandic folklore, Sæmundr is a larger-than-life character who repeatedly tricks the Devil into doing his bidding. For example, in one famous story Sæmundr made a pact with the Devil that the Devil should carry him home to Iceland from Europe in the form of a seal. Sæmundr escaped a diabolical end when, on arrival, he hit the seal on the head with the Bible, and stepped safely ashore.

Although the above is a commonly told story about Sæmundr and his association with the Black School (Svartiskóli or Svartaskóli ), there are several others. In one account, Sæmundr sailed abroad to learn the Dark Arts, but there was no schoolmaster present. Every time the students requested information regarding the arts, books about the subject would be provided the next morning or otherwise be written up on the walls. Above the entrance to the school, it was written: "You may come in; your soul is lost." There was also a law that forbade anyone to study at the school for more than three years. Whenever the students left in a given year, they had to leave at the same time. The devil would keep the last one remaining, and so they always drew lots to determine who would be the last one to leave. On more than one occasion the lot fell on Sæmundr, and so he remained longer than the law permitted. One day, Bishop Jón was traveling through Rome and passed nearby. He found out that Sæmundr was trapped in the Black School, so he offered him advice on how to escape as long as he returned to Iceland and behaved as a good Christian. Sæmundr agreed, but as he and Bishop Jón were leaving the school, the Devil reached up and grabbed Bishop Jón's cloak. Bishop Jón escaped, but the Devil trapped Sæmundr and made him a deal—if Sæmundr could hide for three days, he would be able to return to Iceland. Ultimately, Sæmundr was successful in hiding, and he presumably returned.

Another account explains that when Sæmundr left the Black School, he sewed a leg of mutton into his cloak, and he followed the rushing group out of the doors. When Sæmundr was near the exit, the Devil reached up to grab his cloak but only grabbed the leg that was sewn into the clothing. Sæmundr then dropped the cloak and ran, saying: "He grabbed, but I slipped away!".

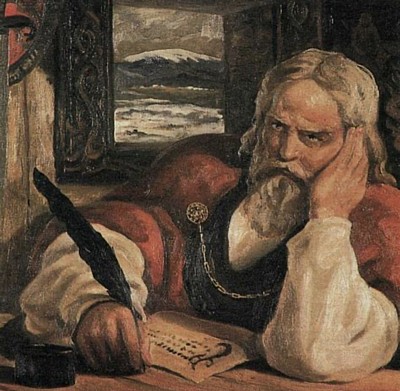

Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson

1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of the Prose Edda, which is a major source for what is today known as Norse mythology, and Heimskringla, a history of the Norse kings that begins with legendary material in Ynglinga saga and moves through to early medieval Scandinavian history. For stylistic and methodological reasons, Snorri is often taken to be the author of Egil's saga. He was assassinated in 1241 by men claiming to be agents of the King of Norway.

Early life

Snorri Sturluson was born in Hvammur í Dölum [is] (commonly transliterated as Hvamm or Hvammr) as a member of the wealthy and powerful Sturlungar clan of the Icelandic Commonwealth, in AD 1179. His parents were Sturla Þórðarson the Elder of Hvammur and his second wife, Guðný Böðvarsdóttir. He had two older brothers, Þórðr (b. 1165) and Sighvatr Sturluson (b. 1170), two sisters (Helga and Vigdís) and nine half-siblings. Snorri was raised from the age of three (or four) by Jón Loftsson, a relative of the Norwegian royal family, in Oddi, Iceland.

As Sturla was trying to settle a lawsuit with the priest and chieftain (Goðorðsmaðr), Páll Sölvason, Páll's wife (Þorbjörg Bjarnardóttir) lunged suddenly at him with a knife—intending, she said, to make him like his one-eyed hero Odin. Before the knife could strike its target, though, bystanders deflected the blow so it hit his cheek instead. The resulting settlement would have beggared Páll, but Jón Loftsson intervened in the Althing to mitigate the judgment and, to compensate Sturla, offered to raise and educate Snorri.

Thus Snorri received an excellent education and forged connections he might not otherwise have been able to. He attended the school of Sæmundr fróði, grandfather of Jón Loftsson, at Oddi, and never returned to his parents' home. His father died in 1183 and his mother (as his guardian) soon squandered Snorri's share of the inheritance. Jón Loftsson died in 1197. The two families then arranged a marriage in 1199 between Snorri and Herdís, the daughter of Bersi Vermundarson. From her father, Snorri inherited an estate at Borg, as well as a chieftainship, and soon acquired more property and additional chieftainships.

Snorri and Herdís were together for four years at Borg. They had at least two children, Hallbera and Jón. Unfortunately, the marriage succumbed to Snorri's philandering, and in 1206, he settled without Herdís in Reykholt as the manager of an estate. He also made significant improvements to the estate, including an outdoor bath fed by hot springs. The bath (known as Snorralaug [is]) and the buildings have been preserved to some extent. During his initial years at Reykholt he fathered another five children, with three different women: Guðrún Hreinsdóttir, Oddný, and Þuríður Hallsdóttir.

Snorri quickly became known as a poet, but was also a lawyer. In 1215, he became lawspeaker of the Althing, the only public office of the Icelandic commonwealth and a position of high respect. In the summer of 1218, he left the lawspeaker position and sailed to Norway, by royal invitation. There he became well acquainted with the teen-aged King Hákon Hákonarson and his co-regent, Jarl Skúli. He spent the winter as house-guest of the jarl. They showered gifts upon him, including the ship in which he sailed, and he in return wrote poetry about them. In the summer of 1219 he met his Swedish colleague, the lawspeaker Eskil Magnusson, and his wife, Kristina Nilsdotter Blake, in Skara. They were both related to royalty and probably gave Snorri an insight into the history of Sweden.

Snorri was mainly interested in history and culture. The Norwegian regents, however, cultivated Snorri, made him a skutilsvein, a senior title roughly equivalent to knight, and received an oath of loyalty. The king hoped to extend his realm to Iceland, which he could do by a resolution of the Althing, of which Snorri had been a key member.

In 1220, Snorri returned to Iceland and by 1222 was back as lawspeaker of the Althing, which he held this time until 1232. The basis of his election was entirely his fame as a poet. Politically he was the king's spokesman, supporting union with Norway, a platform that acquired him enemies among the chiefs. In 1224, Snorri married Hallveig Ormsdottir (c. 1199–1241), a granddaughter of Jón Loftsson, now a widow of great means with two young sons, and made a contract of joint property ownership (or helmingafélag) with her. Their children did not survive to adulthood, but Hallveig's sons and seven of Snorri's children did live to adulthood.

Snorri was the most powerful chieftain in Iceland during the years 1224–1230.

Many of the other chiefs found his position as royal office-holder contrary to their interests, especially the other Sturlungar. Snorri's strategy seems to have been to consolidate power over them, at which point he could offer Iceland to the king. His first moves were civic. On the death in 1222 of Sæmundur, son of Jón Loftsson, he became a suitor for the hand of his daughter, Sólveig. Herdís' silent vote did nothing for his suit. His nephew, Sturla Sighvatsson, Snorri's political opponent, stepped in to marry her in 1223, the year before Snorri met Hallveig.

A period of clan feuding followed. Snorri, perhaps, perceived that only resolute, saga-like actions could achieve his objective, but if so he proved unwilling or incapable of carrying them out. He raised an armed party under another nephew, Böðvar Þórðarson, and another under his son, Órækja, with the intent of executing a first strike against his brother Sighvatur and Sturla Sighvatsson. On the eve of battle he dismissed those forces and offered terms to his brother.

Sighvatur and Sturla with a force of 1000 men drove Snorri into the countryside, where he sought refuge among the other chiefs. Órækja undertook guerrilla operations in the fjords of western Iceland and the war was on.

Haakon IV made an effort to intervene from afar, inviting all the chiefs of Iceland to a peace conference in Norway. This maneuver was transparent to Sighvatur, who understood, as apparently Snorri did not, what could happen to the chiefs in Norway. Instead of killing his opponents he began to insist that they take the king up on his offer.

This was Órækja's fate, who was captured by Sturla during an ostensible peace negotiation at Reykjaholt, and also of Þorleifur Þórðarson, a cousin of Snorri's, who came to his assistance with 800 men and was deserted by Snorri on the battlefield in a flare-up over the chain of command. In 1237, Snorri thought it best to join the king.

The end of Snorri and the Commonwealth

Further information: Age of the Sturlungs

The reign of Haakon IV (Hákon Hákonarson), King of Norway, was troubled by civil war relating to questions of succession and was at various times divided into quasi-independent regions under rival contenders. There were always plots against the king and questions of loyalty but he nevertheless managed to build up the Norwegian state from what it had been.

When Snorri arrived in Norway for the second time, it was clear to the king that he was no longer a reliable agent. The conflict between Haakon and Skúli was beginning to escalate into civil war. Snorri stayed with the jarl, or chieftain, and his son and the jarl made him a jarl hoping to command his allegiance. In August 1238, Sighvatur and four of his sons (Sturla, Markús, Kolbeinn, and Þórður Krókur, the latter two being executed after the battle), were killed at the Battle of Örlygsstaðir in Iceland against Gissur Þorvaldsson and Kolbein the Young, chiefs whom they had provoked. Snorri, Órækja, and Þorleifur requested permission to return home. As the king now could not predict Snorri's behavior, permission was denied. He was explicitly ordered to remain in Norway on the basis of his honorary rank. Skúli on the other hand gave permission and helped them book passage.

Snorri must have had his own ideas about the king's position and the validity of his orders, but at any rate he chose to disobey them; his words according to Sturlunga saga, 'út vil ek' (literally 'out want I', but idiomatically 'I will go home'), have become proverbial in Icelandic. He returned to Iceland in 1239. The king was distracted by the necessity to confront Skúli, who declared himself king in 1239. He was defeated militarily and killed in 1240. Meanwhile, Snorri resumed his chieftainship and made a bid to crush Gissur by prosecuting him in court for the deaths of Sigvat and Sturla. A meeting of the Althing was arranged for the summer of 1241 but Gissur and Kolbein arrived with several hundred men. Snorri and 120 men formed around a church. Gissur chose to pay fines rather than to attack.

Meanwhile, in 1240, after the jarl's defeat, but before his removal from the scene, Haakon sent two agents to Gissur bearing a secret letter with orders to kill or capture Snorri. Gissur was being invited now to join the unionist movement, which he could accept or refuse, just as he pleased. His initial bid to take Snorri at the Althing failed.

Hallveig died of natural causes. When the family bickered over the inheritance, Hallveig's sons, Klaeing and Orm, asked assistance from their uncle Gissur. Holding a meeting with them and Kolbein the Younger, Gissur brought out the letter. Orm refused. Shortly after, Snorri received a letter in cipher runes warning him of the plot, but he could not understand them.[13]

Gissur led seventy men on a daring raid to his house, achieving complete surprise. Snorri Sturluson was assassinated in his house at Reykholt in autumn of 1241. It is not clear that he was given the option of surrender. He fled to the cellar. There, Símon knútur asked Arni the Bitter to strike him. Then Snorri said: Eigi skal höggva!—"Do not strike!" Símon answered: "Högg þú!" — "You strike now!" Snorri replied: Eigi skal höggva!—"Do not strike!" and these were his last words.

This act was not popular in either Iceland or Norway. To diminish the odium, the king insisted that if Snorri had submitted, he would have been spared. The fact that he could make such an argument reveals how far his influence in Iceland had come. Haakon went on suborning the chiefs of Iceland. In 1262, the Althing ratified union with Norway and royal authority was instituted in Iceland. Each member swore an oath of personal loyalty to the king, a practice which continued as each new king came to the throne, until absolute and hereditary monarchy was formally accepted by the Icelanders in 166

Snorri Sturluson's writings provide information and indications concerning persons and events influencing the peoples inhabiting North Europe during periods for which relevant information is scarce: thus, for example, he can be used to illuminate relations between England and Scandinavia during the 10th and 11th centuries. Snorri is considered a figure of enduring importance in this regard, Halvdan Koht describing his work as "surpassing anything else that the Middle Ages have left us of historical literature". He also provided an early account of the discovery of Vinland.

To an extent, the legacy of Snorri Sturluson also played a role in politics long after his death. His writings could be used in support of the claims of later Norwegian kings concerning the venerability and extent of their rule. Later, Heimskringla factored in establishing a national identity during the Norwegian romantic nationalism in mid-19th century.

Icelandic perception of Snorri in the 20th century and to date has been colored by the historical views adopted when Iceland sought to sever its ties with Denmark, any revision of which still has strong nationalistic sentiments to contend with. To serve such views, Snorri and other leading Icelanders of his time are sometimes judged with some presentism, on the basis of concepts that came into vogue only centuries later, such as state, independence, sovereignty, and nation.

Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama studied and translated the Gylfaginning to Spanish, providing a biographic account of Snorri at the prologue.

"Nine worlds I remember", one of the epigraphs to chapter IV of Carl Sagan's Cosmos, is a quotation from Snorri's Edda.

websites

Handrit

Handrit.org is a joint electronic catalogue of manuscripts preserved in the National and University Library of Iceland (Landsbókasafn Íslands – Háskólabókasafn), the Árni Magnússon Institute in Reykjavík (Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum) and the Arnamagnæan Institute in Copenhagen (Den Arnamagnæanske Samling). The catalogue also includes descriptions of manuscripts housed at the Swedish Royal Library (Kungliga biblioteket), the Archives of the Icelandic Alþingi (Skjalasafn Alþingis), the National Museum of Iceland (Þjóðminjasafn Íslands) and the National Archives of Iceland (Þjóðskjalasafn Íslands), as well a number of manuscripts still in private ownership. The manuscripts are primarily Icelandic, but there are also important collections of Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Faroese material, as well as around 100 manuscripts of continental provenance.

Handit.org has its origin in the project Sagnanet, work on which was begun in July of 1997, and in a TEI-compatible XML catalogue developed jointly by the Árni Magnússon Institute in Reykjavík and the Arnamagnæan Institute in Copenhagen in the period 2001−2004. The catalogue was officially launched on 21 April 2010.

The catalogue provides access to a wide range of material from different periods. The earliest items, many of them fragmentary, are from the 12th century and written on parchment, while the later items, which make up the bulk of the collection, are on paper, some from as late as the beginning of the 20th century. The material they preserve includes sagas, poetry, legal, historical, astronomical and medical texts, and much more. It is possible to browse through the material by subject matter.

The website was awarded the University of Iceland’s Hagnýtingarverðlaun (Utilisation award?) in 2010, and has received financial support as part of the ENRICH project (European Networking Resources and Information concerning Cultural Heritage) from the European Commission’s eContent+ programme, the University of Iceland’s Research Fund, the Sigrún Ástrós Sigurðardóttir and Haraldur Sigurðsson Research Fund, the Icelandic Centre for Research (RANNÍS), the National Heritage Fund and the Student’s Innovation Fund.

Icelandic Saga Database

The Icelandic Saga Database is an online resource dedicated to publishing the Sagas of the Icelanders — a large body of medieval Icelandic literature. The sagas are prose histories describing events that took place amongst the Norse and Celtic inhabitants of Iceland during the period of the Icelandic Commonwealth in the 10th and 11th centuries CE.

The Icelandic sagas are believed to have been written in the 13th and 14th centuries CE, perhaps originating in an oral tradition of storytelling. While their facticity and authorship is for the most part unknown, they are a widely recognized gem of world literature thanks to their sparse, succinct prose style and balanced storytelling. The sagas focus largely on history, especially genealogical and family history, and reflect the struggles and conflicts that arose amongst the second and third generations of Norse settlers in medieval Iceland, which was in this time a remote, decentralised society with a rich legal tradition but no organized executive power.

This website contains all the extant Icelandic family sagas. They are accessible in a variety of open formats. The texts use modernised Icelandic orthography. Translations into English and other languages are also made available where these exist in the public domain.

Runor

https://app.raa.se/open/runor/search

Runor is a digital research platform that makes approximately 7,000 runic inscriptions available, as well as reports and images from various databases, institutions and collections.

No country has as many runic inscriptions as Sweden. The purpose of the platform is to simplify research and to make existing runic material digitally accessible, wherever you are in the world. The platform will not require login and the platform is also suited for field work.

Runor contains information about known and registered runes. You can search for rune stones, rune texts and location, geographically via map or place name in the title.

Pdf library with Norse litterature

https://vdoc.pub/search/old%20norse

Founded in 2018 by Cassandre Schimmel, VDOC.PUB has come a long way from its beginnings in university. When Tris Vernice first started out, his passion for place that everyone can sharing knowledge, drove him to quit day job so that VDOC.PUB can offer you this service. We now serve customers all over the world, and are thrilled that we're able to turn our passion into own website.

Perseus CollectionGermanic Materials

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/collection?collection=Perseus%3Acollection%3AGermanic

Since planning began in 1985, the Perseus Digital Library Project has explored what happens when libraries move online. Two decades later, as new forms of publication emerge and millions of books become digital, this question is more pressing than ever. Perseus is a practical experiment in which we explore possibilities and challenges of digital collections in a networked world. For the mission of Perseus and its current research, see here.

Perseus maintains a web site that showcases collections and services developed as a part of our research efforts over the years. The code for the digital library system and many of the collections that we have developed are now available. For more information, please go here.

Our flagship collection, under development since 1987, covers the history, literature and culture of the Greco-Roman world. We are applying what we have learned from Classics to other subjects within the humanities and beyond. We have studied many problems over the past two decades, but our current research centers on personalization: organizing what you see to meet your needs.

An Icelandic-English Dictionary: Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson, Oxford, 1874.

https://old-norse.net/search.php

Cleasby/Vigfusson is the most comprehensive and authoritative dictionary on Old Icelandic.

The copyright on this dictionary is expired. You are welcome to copy this data, post it on other web sites, create derived works, or use the data in any other way you please. As a courtesy, please credit the Germanic Lexicon Project.

Work on this project started in 2003. It was one of the major ongoing projects, with correction work being performed by volunteers worldwide. The goal was to produce a fully corrected document, marked up in XML.

Sean Crist initiated and was directing the project, and also did the OCR, major software design and programming, and ongoing global corrections. There was a hiatus in the project from 2008-2020, but it looks like things are moving forward again.

Scanning and preparation of these page images was made possible by a grant from the American-Scandinavian Foundation.

ONP:Dictionary of Old Norse Prose

https://onp.ku.dk/onp/onp.php?

The Dictionary of Old Norse Prose (ONP) is part of The Arnamagnæan Collection in the Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics (NorS) at the University of Copenhagen (our NorS page is here).

The dictionary is funded through the Arnamagnæan Commission. Read about ONP’s printed publications, orthography, users’ guide, abbreviations and symbols. The word of the day is published on our Twitter feed with a sample definition and citation.

Heimskringla

About the project «Norrøne Tekster og Kvad»

The purpose of the project "Norrøne Tekster og Kvad" (Old Norse Prose and Poetry) is to make Old Norse literature freely accessible on the internet. In addition to source texts in the original language readers will find several texts translated into the later Scandinavian languages, classical scholarly works and other background material, in particular from before 1900.

The project, which is constantly under development, was opened to the public on 1st August 2005. Its aim is to provide a collection of texts that is as comprehensive as possible. The focus is on user-friendliness: all texts have been proofread and documents are available in printable format; keywords can be easily searched. The intention is that "Norrøne Tekster og Kvad" will prove both convenient and useful to serious researcher and amateur enthusiast alike. The project is well under way, but there is still much to be done to complete the task as originally envisaged. The project’s address is www.heimskringla.no .

For copyright reasons a small number of the texts are password-protected and inaccessible to the general public.

The project «Norrøne Tekster og Kvad» seeks working partners

Funding

The "Norrøne Tekster og Kvad" project is a private initiative. It is a non-profit-making concern and exists for the purpose of publishing only. The cost of technical operation and equipment is borne by the owners. Many thousands of working hours have already been put into the project in addition to financial outlay for buying and renting technical equipment and buying in relevant literature. The project is seeking financial subsidy through official and private support agencies and sponsors, and through select advertising and prospective "supporting members".

Naturally, all serious contributors will be credited for their contribution, but it would be financially impossible to pay prospective contributors: the best possible reward is the pleasure and prestige in taking part.

All financial contributions are very gratefully received. If you or your organisation would like to provide financial support, contact us!

The "Norrøne Tekster og Kvad" project seeks volunteer proofreaders

The most arduous and time-consuming work for the project is proofreading. To help with this, contributors will need their own PC or ready access to a PC. Familiarity with using word processing software would be an advantage for beginners in proofreading. It is also important to have a good working knowledge of the Scandinavian languages: Danish, Swedish and Norwegian (Bokmål/Nynorsk) in their older and younger written forms. It would also be an advantage to have some knowledge of Old Norse literature, the Old Norse language, modern Icelandic and Faeroese, although these may not be necessary depending on the actual proofreading to be undertaken. The object will be to compare the digital text on the screen with the printed version: the text will be scanned into the PC using an OCR (Optical Character Recognition) program and these often throw up mistakes which must be corrected manually. The proofread digital text should then be identical with the printed edition. This is an exacting task, which should be carried out with great vigilance. Therefore proofreading is the most important and prestigious contribution that can be made to the project.

Help is also needed with scanning in books for later editing and proofreading. The requirement for text scanning is that volunteers have access to a powerful PC with scanner, and the necessary skills to use the software.

Limitations of the project

The purpose of the project is to draw together as comprehensive a collection of Old Norse literature as is possible: in practice the most limiting aspect is the acquisition of original books and articles. It is obvious that the project cannot be completed in a short space of time. The speed with which this is done, and the breadth and excellence of each area covered, are dependent upon those who are contributing to the project at any one time.

Trusted Academics

Neil Price

Neil Stuppel Price

Born1965 (age 57–58)

Alma materUCL Institute of Archaeology (BA)

Uppsala University (PhD)

Known forThe Viking Way (book)

Scientific career

FieldsArchaeology (especially the Viking Age)

ThesisThe Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia (2002)

Website www.arkeologi.uu.se/Research/Presentations/neil-price/

Neil Stuppel Price is an English archaeologist specialising in the study of Viking Age-Scandinavia and the archaeology of shamanism. He is currently a professor in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University, Sweden.

Born in south-west London, Price went on to gain a BA in Archaeology at the University of London, before writing his first book, The Vikings in Brittany, which was published in 1989. He undertook his doctoral research from 1988 through to 1992 at the University of York, before moving to Sweden, where he completed his PhD at the University of Uppsala in 2002. In 2001, he edited an anthology entitled The Archaeology of Shamanism for Routledge, and the following year published and defended his doctoral thesis, The Viking Way. The Viking Way would be critically appraised as one of the most important studies of the Viking Age and pre-Christian religion by other archaeologists like Matthew Townend and Martin Carver.[1] In 2017 Price was elected a Corresponding Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (CorrFRSE).[2]

Price began his archaeological career in 1983, working for the Museum of London in excavating Roman and Medieval sites around the Greater London area.[3] He subsequently began studying for a BA in the subject in 1988, at the Institute of Archaeology, then a part of the University of London. It was here that he developed a particular interest in the Early Medieval period and the Viking Age, and undertook fieldwork in Britain, Germany, Malta and the Caribbean.[3]

Price started his doctoral research at the University of York's Department of Archaeology from October 1988 through to May 1992. Under the supervision of the archaeologists Steve Roskams and Richard Hall, Price had initially focused his research on the Anglo-Scandinavian tenements at 16–22 Coppergate in York, although eventually moved away from this to focus on archaeology within Scandinavia itself.[4] Personal circumstances meant that Price was unable to finish his doctoral thesis at York, and in 1992 he emigrated to Sweden, where he spent the following five years working as a field archaeologist. Despite his full-time employment, he continued to be engaged in archaeological research in a private capacity, publishing a series of academic papers and presenting others at conferences. In 1996 joined the Department of Archaeology at the University of Uppsala as a research scholar, beginning full-time work there the following year. At Uppsala, he went on to complete his doctoral thesis and gain his PhD under the supervision of Anne-Sofie Gräslund.[5]

Books

The Vikings in Brittany1989Viking Society for Northern Research (London)

The Archaeology of Shamanism2001Routledge (London)

The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia2002Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University (Uppsala)91-506-1626-9

The Viking Way: Religion and War in the Later Iron Age of Scandinavia, 2nd edition2017Oxbow Books (Oxford)978-1-84217-260-5

The Vikings2016Routledge (London & New York)978-0-41534-349-7

Odin's Whisper: Death and the Vikings2016Reaktion Books (London)978-1-78023-290-4

Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings2020Basic Books (New York)978-0-46509-698-5

Articles

Price, Neil & Mortimer, Paul (2004). "An Eye for Odin? Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo". European Journal of Archaeology. European Association of Archaeologists. 17 (3): 517–538. doi:10.1179/1461957113Y.0000000050.

Ursula Drönke

Ursula Miriam Dronke (née Brown, 3 November 1920 – 8 March 2012[1][2]) was a medievalist and former Vigfússon Reader in Old Norse at the University of Oxford and an Emeritus Fellow of Linacre College.[3][4] She also taught at the University of Munich and in the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages at Cambridge University.[2][5]

Born in Sunderland and raised in Newcastle upon Tyne, where her father was a lecturer at Newcastle University, Ursula Brown began her studies as an undergraduate at the University of Tours in 1939, returning to England and enrolling in Somerville College, University of Oxford, after the outbreak of war. She then worked for the Board of Trade until 1946, when she returned to Somerville as a graduate student in Old Norse and beginning in 1950 was a fellow and tutor in English.[2][6] Her Bachelor of Literature thesis on an edition of Þorgils and Hafliða from the Sturlunga saga was passed by J. R. R. Tolkien and Alistair Campbell in July 1949 and formed the basis of a monograph, Þorgils Saga ok Hafliða, published in 1952.[2][7]

In 1960 Brown married fellow medievalist Peter Dronke, and moved with him to the University of Cambridge.[2][8] They collaborated several times, and jointly gave the 1997 H.M. Chadwick Memorial Lecture at the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic.[9]

In the early 1970s, Ursula Dronke was a professor and acting head of Old Norse studies at the University of Munich. In 1976, she was elected Vigfússon Reader in Old Icelandic literature and antiquities at Oxford, and became a research fellow of Linacre College there. She retired and became emeritus Reader and emeritus fellow in 1988. She was able to obtain an endowment from the Rausing family of Sweden to support the Vigfússon Readership in perpetuity.[2]

Dronke's edition of the Poetic Edda with translation and commentary (three volumes published of a projected four) has been praised for its scholarship, insight, and skilful and poetic renderings.[10][11] The series "has completely dominated Eddaic studies worldwide, with the sophistication of its literary analyses and the tremendous breadth of background knowledge brought to bear on the poetry", and in particular, her translation of "Völuspá" "restored it as a work of art."[2] Her collected essays, Myth and Fiction in Early Norse Lands (1996) relate a broad range of early Scandinavian literary and mythological topics to the Indo-European heritage and to medieval European thought, and "[demonstrate] the palpable enthusiasm of a fine scholar and teacher".[2] In 1980 she gave the Dorothea Coke Memorial Lecture for the Viking Society for Northern Research, and she was co-editor of the festschrift for Gabriel Turville-Petre.

Norse Lands (1996) relate a broad range of early Scandinavian literary and mythological topics to the Indo-European heritage and to medieval European thought, and "[demonstrate] the palpable enthusiasm of a fine scholar and teacher".[2] In 1980 she gave the Dorothea Coke Memorial Lecture for the Viking Society for Northern Research, and she was co-editor of the festschrift for Gabriel Turville-Petre.

Selected publications

Editions and translations

- (as Ursula Brown). Þorgils Saga ok Hafliða. Oxford English Monographs 3. London: Oxford, 1952.

- The Poetic Edda Volume I Heroic Poems. Edited with translation, introduction and commentary. Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford University, 1969.

- The Poetic Edda Volume II Mythological Poems. Edited with translation, introduction and commentary. Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford University, 1997. ISBN 0-19-811181-9

The Poetic Edda Volume III Mythological Poems II. Edited with translation, introduction and commentary. Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford University, 2011. ISBN 0-19-811182-7

Other books

- (with Peter Dronke). Barbara et Antiquissima Carmina. Publicaciones del Seminario de Literatura Medieval y Humanística. Barcelona: Universidad Autónoma, Faculdad de Letras, 1977. ISBN 84-600-0992-0

- The Role of Sexual Themes in Njáls Saga: The Dorothea Coke Memorial Lecture in Northern Studies delivered at University College London, 27 May 1980. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1981. (pdf)

- Myth and Fiction in Early Norse Lands. Collected Studies 524. Aldershot, Hampshire/Brookfield, Vermont: Variorum, 1996. ISBN 0-86078-545-9 (Collected articles)

(with Peter Dronke)Growth of Literature: The Sea and the God of the Sea. H.M. Chadwick Memorial Lectures 8. Cambridge: Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, 1997-98. ISBN 978-0-9532697-0-9

Articles

- (with Peter Dronke). "The Prologue of the Prose Edda: Explorations of a Latin Background". Sjötíu ritgerðir helgaðar Jakobi Benediktssyni 20. júlí 1977. Ed. Einar G. Pétursson and Jónas Kristjánsson. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar, 1977. 153-76.

- "The War of the Æsir and the Vanir in Völuspá". Idee, Gestalt, Geschichte: Festschrift Klaus von See. Ed. Gerd Wolfgang Weber. Odense: Odense University, 1988. ISBN 87-7492-697-7. 223-38.

- "Eddic Poetry as a Source for the History of Germanic Religion". Germanische Religionsgeschichte: Quellen und Quellenprobleme. Ed. Heinrich Beck, Detlev Ellmers and Kurt Schier. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 5. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1992. ISBN 3-11-012872-1. 656-84.

- "Pagan Beliefs and Christian Impact: The Contribution of Eddic Studies". Viking Revaluations: Viking Society Centenary Symposium. Ed. Anthony Faulkes and Patrick Thull. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1993. ISBN 0-903521-28-8