Runes & Occultism

The Runes

The Vikings used letters called runes. They are imitations of the Latin letters used in most of Europe during the Viking era. The Latin letters are the ones we use today.

What are runes?

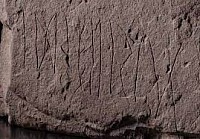

During the first centuries AD, the Romans influenced most of Europe. Runes developed in areas populated by Germanic tribes, probably inspired by the Latin alphabet of the Romans. The earliest runic inscriptions, dating from ca 150 AD, are particularly common in what is now Denmark, Northern Germany and Southern Sweden.

The oldest runes are often found on items such as coins, suit buckles, weapons and implements, and are often the names of the owner of the item or the name of the person who made it.

Runes - an ancient alphabet

The runic alphabet is named after its first six letters:

f – u – þ – a – r – k

The strange þ-rune is pronounced 'th', a sound we find today especially in English words like 'the', 'think' and 'throne'.

Elder Futhark had 24 letters while Younger Futhark, developed at the beginning of the Viking Age, had only 16 letters.

Elder Futhark inscriptions etched by craftsmen and owners have been found on coins, garment brooches, weapons and implements dating primarily from the era of the Iron Age princes.

The runic stones of the Viking Age were erected in commemoration of powerful leaders and their heroic achievements. Short runic inscriptions are also found on everyday artefacts from Viking towns and marketplaces.

Runes were used alongside our present-day alphabet up until the 14th century.

The Vikings did not write on paper, but carved them into stone, wood or iron. The hard materials made it difficult to make round edges, so the runes are more angular than our letters.

At the excavation of the Roskilde 6 long ship, which was found beneath the Museum Island at the Viking Ship Museum, the archaeologists found a runic-stick. Some of the text was lost, but the rest can be read as "Saxe carved these runes, ... man".

Runes are phonetic symbols, just like the letters we use today. The names of individual runes begin with the sound the rune describes, e.g. the m-rune is called maðr, meaning 'man' or 'human being', and the s-rune is called sól, meaning 'sun'.

Runes in the Viking Age

In the Viking Age, runes were used only by the people living in the Nordic area. The Vikings who traveled the world brought the runes with them. There are runic inscriptions written by Vikings in England and as far away as Greece, Turkey, Russia and Greenland.

The runic alphabet of the Viking Age lacks some runes to express all sounds in the language. There are no longer runes for o, d, e and g. The Vikings instead used the runes closest to the sound they were supposed to use.

They could use the u-run for the o-sound, the t-run for the d-sound, the i-run for the e-sound and the k-run for the g-sound.

The Runes

The first systems of writing developed and used by the Norse and other Germanic peoples were runic alphabets. The runes functioned as letters, but they were much more than just letters in the sense in which we today understand the term. Each rune was an ideographic or pictographic symbol of some cosmological principle or power, and to write a rune was to invoke and direct the force for which it stood. Indeed, in every Germanic language, the word “rune” (from Proto-Germanic *runo) means both “letter” and “secret” or “mystery,” and its original meaning, which likely predated the adoption of the runic alphabet, may have been simply “(hushed) message.”

Each rune had a name that hinted at the philosophical and magical significance of its visual form and the sound for which it stands, which was almost always the first sound of the rune’s name. For example, the T-rune, called *Tiwaz in the Proto-Germanic language, is named after the god Tiwaz (known as Tyr in the Viking Age). Tiwaz was perceived to dwell within the daytime sky, and, accordingly, the visual form of the T-rune is an arrow pointed upward (which surely also hints at the god’s prominent role in war). The T-rune was often carved as a standalone ideograph, apart from the writing of any particular word, as part of spells cast to ensure victory in battle.

The runic alphabets are called “futharks” after the first six runes (Fehu, Uruz, Thurisaz, Ansuz, Raidho, Kaunan), in much the same way that the word “alphabet” comes from the names of the first two Semitic letters (Aleph, Beth). There are three principal futharks: the 24-character Elder Futhark, the first fully-formed runic alphabet, whose development had begun by the first century CE and had been completed before the year 400; the 16-character Younger Futhark, which began to diverge from the Elder Futhark around the beginning of the Viking Age (c. 750 CE) and eventually replaced that older alphabet in Scandinavia; and the 33-character Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, which gradually altered and added to the Elder Futhark in England. On some inscriptions, the twenty-four runes of the Elder Futhark were divided into three ættir (Old Norse, “families”) of eight runes each, but the significance of this division is unfortunately unknown.

Runes were traditionally carved onto stone, wood, bone, metal, or some similarly hard surface rather than drawn with ink and pen on parchment. This explains their sharp, angular form, which was well-suited to the medium.

Much of our current knowledge of the meanings the ancient Germanic peoples attributed to the runes comes from the three “Rune Poems,” documents from Iceland, Norway, and England that provide a short stanza about each rune in their respective futharks (the Younger Futhark is treated in the Icelandic and Norwegian Rune Poems, while the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc is discussed in the Old English Rune Poem).

THE ORIGINS OF THE RUNES

While runologists argue over many of the details of the historical origins of runic writing, there is widespread agreement on a general outline. The runes are presumed to have been derived from one of the many Old Italic alphabets in use among the Mediterranean peoples of the first century CE, who lived to the south of the Germanic tribes. Earlier Germanic sacred symbols, such as those preserved in northern European rock carvings, were also likely influential in the development of the script.

The earliest possibly runic inscription that we know of is found on the Meldorf brooch, which was manufactured in the north of modern-day Germany around 50 CE. The inscription is highly ambiguous, however, and scholars are divided over whether its letters are runic or Roman. The earliest unambiguous runic inscriptions are found on the Vimose comb from Vimose, Denmark and the Øvre Stabu spearhead from southern Norway, both of which date to approximately 160 CE. The earliest known carving of the entire futhark (alphabet), in order, is that on the Kylver stone from Gotland, Sweden, which dates to roughly 400 CE.

The transmission of writing from southern Europe to northern Europe likely took place via Germanic warbands, the dominant northern European military institution of the period, who would have encountered Italic writing firsthand during campaigns amongst their southerly neighbors. This hypothesis is supported by the association that runes have always had with the god Odin, who, in the Proto-Germanic period, under his original name *Woðanaz, was the divine model of the human warband leader and the invisible patron of the warband’s activities. The Roman historian Tacitus tells us that Odin (“Mercury” in the interpretatio romana) was already established as the dominant god in the pantheons of many of the Germanic tribes by the first century. Whether the runes and the cult of Odin arose together, or whether the latter predated the former, is of little consequence for our purposes here. As esteemed Indo-European scholar Georges Dumézil notes:

If Odin was first and always the highest magician, we realize that the runes, however recent they may be, would have fallen under his sway. New and particularly effective implements for magic works, they would become by definition and without contest a part of his domain. … Odin could have been the patron, the possessor par excellence of this redoubtable power of secrecy and secret knowledge, before the name of that knowledge became the technical name of signs both phonetic and magic which came from the Alps or elsewhere, but did not lose its former, larger sense.

From the perspective of the ancient Germanic peoples themselves, however, the runes came from no source as mundane as an Old Italic alphabet. The runes were never “invented,” but are instead eternal, pre-existent forces that Odin himself discovered by undergoing a tremendous ordeal. This tale has come down to us in the Old Norse poem Hávamál (“The Sayings of the High One”):

I know that I hung

On the wind-blasted tree

All of nights nine,

Pierced by my spear

And given to Odin,

Myself sacrificed to myself

On that pole

Of which none know

Where its roots run.

No aid I received,

Not even a sip from the horn.

Peering down,

I took up the runes –

Screaming I grasped them –

Then I fell back from there.

The tree from which Odin hangs himself is surely none other than Yggdrasil, the world-tree at the center of the Germanic cosmos whose branches and roots hold the Nine Worlds. Directly below the world-tree is the Well of Urd, a source of incredible wisdom. The runes themselves seem to have their native dwelling-place in its waters. This is also suggested by another Old Norse poem, the Völuspá (“Insight of the Seeress”):

There stands an ash called Yggdrasil,

A mighty tree showered in white hail.

From there come the dews that fall in the valleys.

It stands evergreen above Urd’s Well.

From there come maidens, very wise,

Three from the lake that stands beneath the pole.

One is called Urd, another Verdandi,

Skuld the third; they carve into the tree

The lives and fates of children.

These “three maidens” are the Norns, and their carvings surely consist of runes. We therefore have a clear association between the Well of Urd, the runes, and magic – in this case, the ability of the Norns to carve the fates of all beings.

Presumably, then, after Odin discovered the runes by ritually sacrificing himself to himself and fasting for nine days while staring into the waters of the Well of Urd, it was he who imparted the runes to the first human runemasters. His paradigmatic sacrifice was likely symbolically imitated in initiation ceremonies during which the candidate learned the lore of the runes, but, unfortunately, no concrete evidence of such a practice has survived into our times.

RUNIC PHILOSOPHY AND MAGIC

In the pre-Christian Germanic worldview, the spoken word possesses frightfully strong creative powers. As Scandinavian scholar Catharina Raudvere notes, “The pronouncement of words was recognized to have a tremendous influence over the concerns of life. The impact of a sentence uttered aloud could not be questioned and could never be taken back – as if it had become somehow physical. … Words create reality, not the other way around.” This is, in an important sense, an anticipation of the philosophy of language advanced by the twentieth-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger in his seminal essay Language. For Heidegger, language is an inescapable structuring element of perception. Words don’t merely reflect our perception of the world; rather, we perceive and experience the world in the particular ways that our language demands of us. Thinking outside of language is literally unthinkable, because all thought takes place within language – hence the inherent, godlike creative powers of words. In traditional Germanic society, to vocalize a thought is to make that thought part of the fabric of reality, altering reality accordingly – perhaps not absolutely, but in some important measure.

Each of the runes represents a phoneme – the smallest unit of sound in a language, such as “t,” “s,” “r,” etc. – and as such is a transposition of a phoneme into a visual form.

Most modern linguists take it for granted that the relationship between the signified (the concrete reality referred to by a word) and the signifier (the sounds used to vocalize that word) is arbitrary. However, a minority of linguists embrace an opposing theory known as “phonosemantics:” the idea that there is, in fact, a meaningful connection between the sounds that make up a word and the word’s meaning. To put this another way, the phoneme itself carries an inherent meaning. The meaning of the word “thorn,” for example, derives in large part from the combined meaning of the phonemes “th,” “o,” “r,” and “n.”

The phonosemantic view of language is in agreement with the traditional northern European view, where “words create reality, not the other way around.” The runes, as transpositions of phonemes, bring the inherent creative powers of speech into a visual medium. We’ve already noted that the word “rune” means “letter” only secondarily, and that its primary meaning is “secret” or “mystery” – the mysterious power carried by the phoneme itself. We must also remember the ordeal Odin undertook in order to discover the runes – no one would hang from a tree without food or water for nine days and nights, ritually wounded by his own spear, in order to obtain a set of arbitrary signifiers.

With the runes, the phonosemantic perspective takes on an additional layer of significance. Not only is the relationship between the definition of a word and the phonemes that comprise it inherently meaningful – the relationship between a phoneme and its graphic representation is inherently meaningful as well.

Thus, the runes were not only a means of fostering communication between two or more humans. Being intrinsically meaningful symbols that could be read and understood by at least some nonhuman beings, they could facilitate communication between humankind and the invisible powers who animate the visible world, providing the basis for a plethora of magical acts.

In the verses from the Völuspá quoted above, we see that the carving of runes is one of the primary means by which the Norns establish the fate of all beings (the other most often-noted method being weaving). Given that the ability to alter the course of fate is one of the central concerns of traditional Germanic magic, it should come as no surprise that the runes, as an extremely potent means of redirecting fate, and as inherently meaningful symbols, were thereby inherently magical by their very nature. This is a controversial statement to make nowadays, since some scholars insist that, while the runes may have sometimes been used for magical purposes, they were not, in and of themselves, magical.

But consider the following episode from Egil’s Saga. While traveling, Egil eats a meal with a farmer whose house is on the Viking’s route. The farmer’s daughter is dangerously ill, and he asks Egil for help. When Egil examines the girl’s bed, he finds a whalebone with runes carved on it. The farmer explains to Egil that these runes were carved by the son of a local farmer – presumably an ignorant, illiterate person whose knowledge of the runes could have only been flimsy at best. Egil, being a master of runic lore, readily discerns that this inscription is the cause of the girl’s woes. After destroying the inscription by scraping the runes off into the fire and burning the whalebone itself (!), Egil carves a different message in different runes so as to counteract the malignancy of the earlier writing. After this has been accomplished, the girl recovers.

We can see from this incident that the heathen northern Europeans made a sharp distinction between the powers of the runes themselves, and the uses to which they were put. While the body of surviving runic inscriptions and literary descriptions of their use definitely suggest that the runes were sometimes put to profane, silly, and/or ignorant purposes, the Eddas and sagas make it abundantly clear that the signs themselves do possess immanent magical attributes that work in particular ways regardless of the intended uses to which they’re put by humans.

THE MEANINGS OF THE RUNES

This section provides the sign, name, phoneme (sound), and short description of the meaning of each of the twenty-four runes that comprise the Elder Futhark. The given meanings are based on the medieval Rune Poems exclusively. Where our present knowledge isn’t extensive enough to give an explanation of which one can be reasonably certain, this is noted and the meaning is left unexplained or only partially explained. This article is hardly the place for esoteric speculations, which have been avoided. (If you’re interested in going beyond the evidence and using less academically acceptable means of discerning other meanings of the runes, you have to do that yourself.

ᚠ Name: Fehu, “cattle.” Phoneme: F. Meaning: wealth.

ᚢ Name: Uruz, “aurochs.” Phoneme: U (long and/or short). Meaning: strength of will.

ᚦ Name: Thurisaz, “Giant” Phoneme: Th (both soft and hard). Meaning: danger, suffering.

ᚨ Name: Ansuz, “an Æsir god.” Phoneme: A (long and/or short). Meaning: prosperity, vitality.

ᚱ Name: Raidho, “journey on horseback.” Phoneme: R. Meaning: movement, work, growth.

ᚲ Name: Kaunan, “ulcer.” Phoneme: K. Meaning: mortality, pain.

ᚷ Name: Gebo, “gift.” Phoneme: G. Meaning: generosity.

ᚹ Name: Wunjo, “joy.” Phoneme: W. Meaning: joy, ecstasy.

ᚺ Name:Hagalaz, “hail.” Phoneme: H. Meaning: destruction, chaos.

ᚾ Name: Naudhiz, “need.” Phoneme: N. Meaning: need, unfulfilled desire.

ᛁ Name: Isaz, “ice.” Phoneme: I (long and/or short). Meaning: unknown (the rune poems are ambiguous and contradictory).

ᛃ Name: Jera, “year.” Phoneme: Germanic J, modern English Y. Meaning: harvest, reward.

ᛇ Name: Eihwaz, “yew.” Phoneme: I pronounced like “Eye.” Meaning: strength, stability.

ᛈ Name: unknown. Phoneme: P. Meaning: unknown. (Note: the theory that this rune’s name was “Pertho” is just speculation. No one really knows, because the Viking Age and medieval sources are too vague.)

ᛉ Name: unknown (the rune poems are contradictory). Phoneme: Z. Meaning: protection from enemies, defense of that which one loves.

ᛋ Name: Sowilo, “sun.” Phoneme: S. Meaning: success, solace.

ᛏ Name: Tiwaz, “the god Tiwaz.” Phoneme: T. Meaning: victory, honor.

ᛒ Name: Berkanan, “birch.” Phoneme: B. Meaning: fertility, growth, sustenance.

ᛖ Name: Ehwaz, “horse.” Phoneme: E (long and/or short). Meaning: trust, faith, companionship.

ᛗ Name: Mannaz, “man.” Phoneme: M. Meaning: augmentation, support.

ᛚ Name: Laguz. Phoneme: L. Meaning: formlessness, chaos, potentiality, the unknown.

ᛜ Name: Ingwaz, “the god Ingwaz.” Phoneme: Ng. Meaning: fertilization, the beginning of something, the actualization of potential.

ᛟ Name: Othalan, “inheritance.” Phoneme: O (long and/or short). Meaning: inheritance, heritage, tradition, nobility.

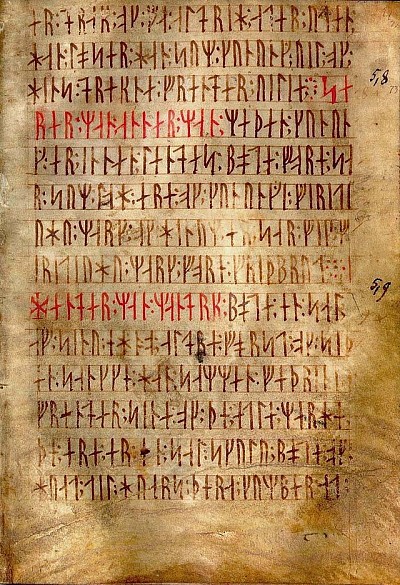

The Rune Poems

The Rune Poems were a recitation of the names and kennings (associations) of the runes. They were presumably used as an aid in memorizing and transmitting the lore. There are three of the old poems known; the Icelandic, the Norwegian, and the Anglo-Saxon. The Anglo-Saxon shows considerable influence from Christianity. There was probably a poem for the Elder Futhark, but it has not come down to us. The Elder Futhark consisted of twenty four runes. Around 800 CE or so the Scandinavians reduced the number to sixteen, while the Anglo Saxons increased the number to accomode different sounds in their language.

The Abecedarium Nordmannicum, (~825CE) might be considered a fourth Old Saxon verson, but is quite fragmentory.

The versions cited, with their English translation, were taken from the book "Runic and Heroic Poems" by Bruce Dickins. The book was published in 1915, and I believe that it has passed into public domain. If you can find a copy, do so. It's excellent.

The most traditional is probably the Icelandic Rune Poem, and it’s English translation. The stanzas in the Norwegian Rune Poem are each links to the corresponding stanza in its English translation. The Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem with its English translation.

Most who have written on the meanings of the runes recently have a background and interest in New Age mysticism, Mediterranean style magick, or some other belief structure not part of the historical Nordic mentality. This affects their interpretation. Most mainstream scholars avoid the subject entirely because of the New Age taint. This means that if you are interested in how the Vikings saw the runes (rather than the New Age, or modern Asatru folks), you should go the original sources as much as possible, and not rely on someone else's interpretation. Read the runic poems, the eddas, the sagas, and other period sources for yourself. I did find a discussion in Finland that might serve as a good starting point on the traditional meanings of the runes.

The Icelandic Rune Poem(in Old Icelandic)

Fé er frænda rógok flæðar viti

ok grafseiðs gata

aurum fylkir.

Úr er skýja grátrok skára þverrir

ok hirðis hatr.

umbre vísi

Þurs er kvenna kvölok kletta búi

ok varðrúnar verr.

Saturnus þengill.

Óss er algingautrok ásgarðs jöfurr,

ok valhallar vísi.

Jupiter oddviti.

Reið er sitjandi sælaok snúðig ferð

ok jórs erfiði.

iter ræsir.

Kaun er barna bölok bardaga [för]

ok holdfúa hús.

flagella konungr.

Hagall er kaldakornok krapadrífa

ok snáka sótt.

grando hildingr.

Nauð er Þýjar þráok þungr kostr

ok vássamlig verk.

opera niflungr.

Íss er árbörkrok unnar þak

ok feigra manna fár.

glacies jöfurr.

Ár er gumna góðiok gott sumar

algróinn akr.

annus allvaldr.

Sól er skýja skjöldrok skínandi röðull

ok ísa aldrtregi.

rota siklingr.

Týr er einhendr ássok ulfs leifar

ok hofa hilmir.

Mars tiggi.

Bjarkan er laufgat limok lítit tré

ok ungsamligr viðr.

abies buðlungr.

Maðr er manns gamanok moldar auki

ok skipa skreytir.

homo mildingr.

Lögr er vellanda vatnok viðr ketill

ok glömmungr grund.

lacus lofðungr.

Ýr er bendr bogiok brotgjarnt járn

ok fífu fárbauti.

arcus ynglingr.

The Icelandic Rune Poem(in Modern English)

Wealth

source of discord among kinsmen

and fire of the sea

and path of the serpent.

Shower

lamentation of the clouds

and ruin of the hay-harvest

and abomination of the shepherd.

Giant

torture of women

and cliff-dweller

and husband of a giantess.

God

aged Gautr

and prince of Ásgarðr

and lord of Vallhalla.

Riding

joy of the horsemen

and speedy journey

and toil of the steed.

Ulcer

disease fatal to children

and painful spot

and abode of mortification.

Hail

cold grain

and shower of sleet

and sickness of serpents.

Constraint

grief of the bond-maid

and state of oppression

and toilsome work.

Ice

bark of rivers

and roof of the wave

and destruction of the doomed.

Plenty

boon to men

and good summer

and thriving crops.

Sun shield of the clouds

and shining ray

and destroyer of ice.

Týr

god with one hand

and leavings of the wolf

and prince of temples.

Birch

leafy twig

and little tree

and fresh young shrub.

Man

delight of man

and augmentation of the earth

and adorner of ships.

Water

eddying stream

and broad geysir

and land of the fish.

Yew

bent bow

and brittle iron

and giant of the arrow.

The Norwegian Rune PoemIn Original Old Norse

Fé vældr frænda róge;

føðesk ulfr í skóge.

Úr er af illu jarne;

opt løypr ræinn á hjarne.

Þurs vældr kvinna kvillu;

kátr værðr fár af illu.

Óss er flæstra færða

fo,r; en skalpr er sværða.

Ræið kveða rossom væsta;

Reginn sló sværðet bæzta.

Kaun er barna bo,lvan;

bo,l gørver nán fo,lvan.

Hagall er kaldastr korna;

Kristr skóp hæimenn forna.

Nauðr gerer næppa koste;

nøktan kælr í froste.

Ís ko,llum brú bræiða;

blindan þarf at læiða.

Ár er gumna góðe;

get ek at o,rr var Fróðe.

Sól er landa ljóme;

lúti ek helgum dóme.

Týr er æinendr ása;

opt værðr smiðr blása.

Bjarkan er laufgrønstr líma;

Loki bar flærða tíma.

Maðr er moldar auki;

mikil er græip á hauki.

Lo,gr er, fællr ór fjalle

foss; en gull ero nosser.

Ýr er vetrgrønstr viða;

vænt er, er brennr, at sviða.

The Norwegian Rune PoemIn Modern English

Wealth is a source of discord among kinsmen;

the wolf lives in the forest.

Dross comes from bad iron;

the reindeer often races over the frozen snow.

Giant causes anguish to women;

misfortune makes few men cheerful.

Estuary is the way of most journeys;

but a scabbard is of swords.

Riding is said to be the worst thing for horses;

Reginn forged the finest sword.

Ulcer is fatal to children;

death makes a corpse pale.

Hail is the coldest of grain;

Christ created the world of old.

Constraint gives scant choice;

a naked man is chilled by the frost.

Ice we call the broad bridge;

the blind man must be led.

Plenty is a boon to men;

I say that Frothi was generous.

Sun is the light of the world;

I bow to the divine decree.

Tyr is a one-handed god;

often has the smith to blow.

Birch has the greenest leaves of any shrub;

Loki was fortunate in his deceit.

Man is an augmentation of the dust;

great is the claw of the hawk.

A waterfall is a River which falls from a mountain-side;

but ornaments are of gold.

Yew is the greenest of trees in winter;

it is wont to crackle when it burns.

The Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem(in Anglo-Saxon)

Feoh byþ frofur fira gehwylcum;sceal ðeah manna gehwylc miclun hyt dælan

gif he wile for drihtne domes hleotan.

Ur byþ anmod ond oferhyrned,felafrecne deor, feohteþ mid hornum

mære morstapa; þæt is modig wuht.

Ðorn byþ ðearle scearp; ðegna gehwylcumanfeng ys yfyl, ungemetum reþe

manna gehwelcum, ðe him mid resteð.

Os byþ ordfruma ælere spræce,wisdomes wraþu ond witena frofur

and eorla gehwam eadnys ond tohiht.

Rad byþ on recyde rinca gehwylcumsefte ond swiþhwæt, ðamðe sitteþ on ufan

meare mægenheardum ofer milpaþas.

Cen byþ cwicera gehwam, cuþ on fyreblac ond beorhtlic, byrneþ oftust

ðær hi æþelingas inne restaþ.

Gyfu gumena byþ gleng and herenys,wraþu and wyrþscype and wræcna gehwam

ar and ætwist, ðe byþ oþra leas.

Wenne bruceþ, ðe can weana lytsares and sorge and him sylfa hæfþ

blæd and blysse and eac byrga geniht.

Hægl byþ hwitust corna; hwyrft hit of heofones lyfte,wealcaþ hit windes scura; weorþeþ hit to wætere syððan.

Nyd byþ nearu on breostan; weorþeþ hi þeah oft niþa bearnumto helpe and to hæle gehwæþre, gif hi his hlystaþ æror.

Is byþ ofereald, ungemetum slidor,glisnaþ glæshluttur gimmum gelicust,

flor forste geworuht, fæger ansyne.

Ger byÞ gumena hiht, ðonne God læteþ,halig heofones cyning, hrusan syllan

beorhte bleda beornum ond ðearfum.

Eoh byþ utan unsmeþe treow,heard hrusan fæst, hyrde fyres,

wyrtrumun underwreþyd, wyn on eþle.

Peorð byþ symble plega and hlehterwlancum [on middum], ðar wigan sittaþ

on beorsele bliþe ætsomne.

Eolh-secg eard hæfþ oftust on fennewexeð on wature, wundaþ grimme,

blode breneð beorna gehwylcne

ðe him ænigne onfeng gedeþ.

Sigel semannum symble biþ on hihte,ðonne hi hine feriaþ ofer fisces beþ,

oþ hi brimhengest bringeþ to lande.

Tir biþ tacna sum, healdeð trywa welwiþ æþelingas; a biþ on færylde

ofer nihta genipu, næfre swiceþ.

Beorc byþ bleda leas, bereþ efne swa ðeahtanas butan tudder, biþ on telgum wlitig,

heah on helme hrysted fægere,

geloden leafum, lyfte getenge.

Eh byþ for eorlum æþelinga wyn,hors hofum wlanc, ðær him hæleþ ymb[e]

welege on wicgum wrixlaþ spræce

and biþ unstyllum æfre frofur.

Man byþ on myrgþe his magan leof:sceal þeah anra gehwylc oðrum swican,

forðum drihten wyle dome sine

þæt earme flæsc eorþan betæcan.

Lagu byþ leodum langsum geþuht,gif hi sculun neþan on nacan tealtum

and hi sæyþa swyþe bregaþ

and se brimhengest bridles ne gym[eð].

Ing wæs ærest mid East-Denumgesewen secgun, oþ he siððan est

ofer wæg gewat; wæn æfter ran;

ðus Heardingas ðone hæle nemdun.

Eþel byþ oferleof æghwylcum men,gif he mot ðær rihtes and gerysena on

brucan on bolde bleadum oftast.

Dæg byþ drihtnes sond, deore mannum,mære metodes leoht, myrgþ and tohiht

eadgum and earmum, eallum brice.

Ac byþ on eorþan elda bearnumflæsces fodor, fereþ gelome

ofer ganotes bæþ; garsecg fandaþ

hwæþer ac hæbbe æþele treowe.

Æsc biþ oferheah, eldum dyrestiþ on staþule, stede rihte hylt,

ðeah him feohtan on firas monige.

Yr byþ æþelinga and eorla gehwæswyn and wyrþmynd, byþ on wicge fæger,

fæstlic on færelde, fyrdgeatewa sum.

Iar byþ eafix and ðeah a bruceþfodres on foldan, hafaþ fægerne eard

wætre beworpen, ðær he wynnum leofaþ.

Ear byþ egle eorla gehwylcun,ðonn[e] fæstlice flæsc onginneþ,

hraw colian, hrusan ceosan

blac to gebeddan; bleda gedreosaþ,

wynna gewitaþ, wera geswicaþ.

The Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem(in Modern English)

Wealth is a comfort to all men;yet must every man bestow it freely,

if he wish to gain honour in the sight of the Lord.

The aurochs is proud and has great horns;it is a very savage beast and fights with its horns;

a great ranger of the moors, it is a creature of mettle.

The thorn is exceedingly sharp,an evil thing for any knight to touch,

uncommonly severe on all who sit among them.

The mouth is the source of all language,a pillar of wisdom and a comfort to wise men,

a blessing and a joy to every knight.

Riding seems easy to every warrior while he is indoorsand very courageous to him who traverses the high-roads

on the back of a stout horse.

The torch is known to every living man by its pale, bright flame;it always burns where princes sit within.

Generosity brings credit and honour, which support one's dignity;it furnishes help and subsistence

to all broken men who are devoid of aught else.

Bliss he enjoys who knows not suffering, sorrow nor anxiety,and has prosperity and happiness and a good enough house.

Hail is the whitest of grain;it is whirled from the vault of heaven

and is tossed about by gusts of wind

and then it melts into water.

Trouble is oppressive to the heart;yet often it proves a source of help and salvation

to the children of men, to everyone who heeds it betimes.

Ice is very cold and immeasurably slippery;it glistens as clear as glass and most like to gems;

it is a floor wrought by the frost, fair to look upon.

Summer is a joy to men, when God, the holy King of Heaven,suffers the earth to bring forth shining fruits

for rich and poor alike.

The yew is a tree with rough bark,hard and fast in the earth, supported by its roots,

a guardian of flame and a joy upon an estate.

Peorth is a source of recreation and amusement to the great,where warriors sit blithely together in the banqueting-hall.

The Eolh-sedge is mostly to be found in a marsh;it grows in the water and makes a ghastly wound,

covering with blood every warrior who touches it.

The sun is ever a joy in the hopes of seafarerswhen they journey away over the fishes' bath,

until the courser of the deep bears them to land.

Tiw is a guiding star; well does it keep faith with princes;it is ever on its course over the mists of night and never fails.

The poplar bears no fruit; yet without seed it brings forth suckers,for it is generated from its leaves.

Splendid are its branches and gloriously adorned

its lofty crown which reaches to the skies.

The horse is a joy to princes in the presence of warriors.A steed in the pride of its hoofs,

when rich men on horseback bandy words about it;

and it is ever a source of comfort to the restless.

The joyous man is dear to his kinsmen;yet every man is doomed to fail his fellow,

since the Lord by his decree will commit the vile carrion to the earth.

The ocean seems interminable to men,if they venture on the rolling bark

and the waves of the sea terrify them

and the courser of the deep heed not its bridle.

Ing was first seen by men among the East-Danes,till, followed by his chariot,

he departed eastwards over the waves.

So the Heardingas named the hero.

An estate is very dear to every man,if he can enjoy there in his house

whatever is right and proper in constant prosperity.

Day, the glorious light of the Creator, is sent by the Lord;it is beloved of men, a source of hope and happiness to rich and poor,

and of service to all.

The oak fattens the flesh of pigs for the children of men.Often it traverses the gannet's bath,

and the ocean proves whether the oak keeps faith

in honourable fashion.

The ash is exceedingly high and precious to men.With its sturdy trunk it offers a stubborn resistance,

though attacked by many a man.

Yr is a source of joy and honour to every prince and knight;it looks well on a horse and is a reliable equipment for a journey.

Iar is a river fish and yet it always feeds on land;it has a fair abode encompassed by water, where it lives in happiness.

The grave is horrible to every knight,when the corpse quickly begins to cool and is laid in the bosom of the dark earth. Prosperity declines, happiness passes away and covenants are broken

Reccomended Books on Runes

Runes a handbook

By Michael P. Barnes

Offers a full introduction to and survey of runes and runology: their history, how they were used, and their interpretation. Runes, often considered magical symbols of mystery and power, are in fact an alphabetic form of writing. Derived from one or more Mediterranean prototypes, they were used by Germanic peoples to write different kinds of Germanic language, principally Anglo-Saxon and the various Scandinavian idioms, and were carved into stone, wood, bone, metal, and other hard surfaces; types of inscription range from memorials to the dead, through Christian prayers and everyday messages to crude graffiti. First reliably attested in the second century AD, runes were in due course supplanted by the roman alphabet, though in Anglo-Saxon England they continued in use until the early eleventh century, inScandinavia until the fifteenth (and later still in one or two outlying areas). This book provides an accessible, general account of runes and runic writing from their inception to their final demise. It also covers modern uses of runes, and deals with such topics as encoded texts, rune names, how runic inscriptions were made, runological method, and the history of runic research. A final chapter explains where those keen to see runic inscriptions can most easily find them. Professor MICHAEL P, BARNES is Emeritus Professor of Scandinavian Studies, University College London.

Occultism

The Icelandic grimores

The tradition of Icelandic galdrabækur developed in the so-called lærdómsöld (1550–1750), which – despite its name – was rather a period of superstition. The Reformation took place in Iceland before the middle of the 16th century and the Lutheran church was imposed by the Danish crown. From this moment on, the crown and the church determined what books may be read. In this climate, a popular culture, strongly influenced by superstition and magic, developed far away from the official institutions. At this time, the hunt for witches began on Iceland. In approximately half of the witchcraft trials (62 out of 130) that took place between 1554 and 1719, galdrastafir (also called galdramyndir) and galdrabækur are mentioned amongst the tools used to perform magic rites.[1] For this reason, one can imagine that during this period, many manuscripts were secretly burnt and destroyed by their owners in order to be safe from suspicion of practicing sorcery.

The oldest specimen of a grimoire containing galdrastafir dates from the beginning of the 16th century. The manuscript AM 434a 12mo contains a medical book, written by two copyists, but only a fragment of this booklet survives.[2] It shows a clear connection with the tradition of the herbarium (Urtebog) written by the Danish scholar Henrik Harpestræng (†1244).[3] At the very beginning (fols 1r–6v), however, it contains an otherwise unknown supplement displaying galdrastafir, which is the oldest example of a Scandinavian grimoire combining textual and visual communication.

Another old grimoire is the so-called Galdrabók, dating from the latter part of the 1500s and now preserved in Stockholm.[4] This is a collection of 47 randomly arranged spells giving an insight into magic practices. As the borders between ‘white’ and ‘black’ magic must often be considered as fluid, it is difficult to specify the kind of magic. As a matter of fact, a great number of charms are not meant to act against someone or something, but rather to provide protection for someone. They combine spells, magic charms, Christian prayers and formulae and practices for self-protection or for harming others, and they record a lot of different galdrastafir, as well as seals (insigli).

Generally speaking, the function of all Icelandic grimoires was to protect one’s own person rather than harm others. They contain two kinds of charms: a first group was meant to assist the user in pursuing specific goals (e.g., becoming invisible, catching a thief, or winning a woman’s love); the second group are represented by the insigli, or ‘seals’, which like amulets, provided protection to the persons who carried them. Unlike the other galdrastafir, the seals display a geometrical form, mostly a round one, which closely resembles the shape of the well-known Vegvísir and ægishjálmur. Whilst some of the charms do not have any religious reference, some others display aspects of Christian superstition.

The Icelandic examples had parallels on the Continent. Among the most popular works, known throughout Europe, we find Clavicula Salomonis, Corpus Hermeticum, De Occulta Philosophia, and The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses. They all purport to contain ancient knowledge allegedly going back to the times of King Solomon or even the ancient god Hermes Trismegistos. Some of them offer instructions how to summon helping spirits or ward off evil demons, using potions, remedies or magical objects, how to make humans invisible, or to kill the livestock of one’s enemies. Unusual and rare ingredients (i.e., wool of the oldest castrated animal, bowels of a flatfish, wagtail tongues, skin of a freshly excavated corpse, and many others) should be collected (as well as pestled, burned, cooked, knotted together, or buried), often at distinct points in time like midnight, at a full or new moon, or at special feast days (such as Christmas, New Year’s day, or a particular Saint’s day). Astrology, alchemy, plant science, and medicine play a relevant role. Such books were printed despite the prohibitions imposed by the official church, and found a wide distribution nonetheless.

In Landsbókasafn Íslands, several grimoires are preserved (see: www.handrit.is). However, these documents date from a much later period and appear to be copies of copies, yet showing a distinct affinity with the older tradition.

The most comprehensive collection of galdrastafir is preserved in Lbs 2413 8vo, which dates from about 1800. This manuscript of uncertain provenance consists of 74 sheets. It lists about 200 examples of spells and charms; in each case, written text is closely connected with a visual element (galdramynd), and only the combination of the two parts produces meaning. The use of different kinds of writing systems was probably meant to amplify the effect of the charms.

Considering that possession of such books represented a real danger for their owners, it is quite probable that many additional manuscripts were intentionally destroyed as a precaution.

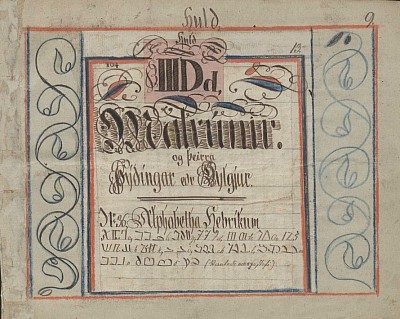

Script: Huld - ÍB 383 4to

The Huld manuscript was written in 1847 by Geir Vigfússon in Akureyri (died 1880). As many later grimoires the main material is a collection of typefaces, both secret letters and rune letters, althogether around 300 alphabets. Geir has had models of at least three old manuscripts and mentions that one of them was written in Seltjarnarnes around 1810. In the second part of the book, there are 30 magic staves with texts.

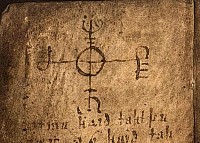

The book of Hlíðarendi - AM 158 4to

Icelandic magic staves are often dervied from ancient runes. They have been known since long before the age of witch-hunts and are sometimes to be found on the margins of old manuscripts. This is the case with this particular mamuscript made of animal hide dating from around 1500 and goes by the name of the Book of Hlíðarendi (Hlíðarendabók).

The book contains the book of John and various laws. Legal texts were usually more ambitious and so they have been preserved better than sagas. On this page of the manuscript a stave has been drawn below the text and then an attempt made to scrape it off the page.

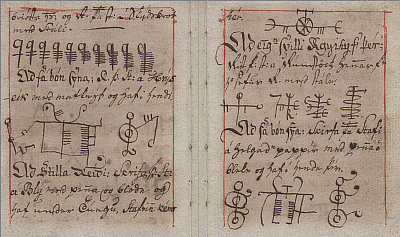

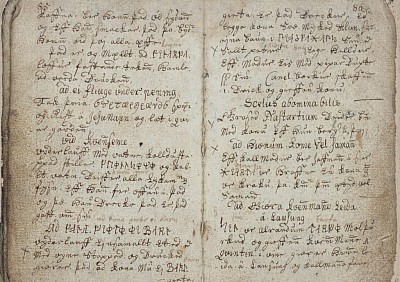

Grimoire dating from around 1820

Grimoires tell the reader how to perform strange things. This particular grimoire teaches you how to make your cat become full with kittens without mating, to make fish gather in one and the same place, to make husband and wife stay together and be happy, and how to identify a signal of death.

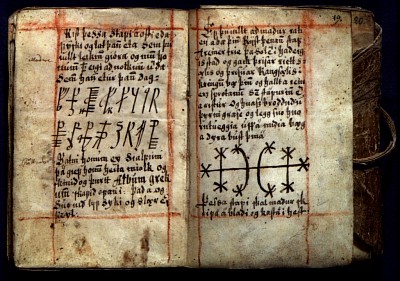

The Stockholm grimoire Lbs 764 4to

Some grimoires have speech runes and many typefaces. Most of these books are from later centuries although speech runes, band runes and lettering is to be found in earlier manuscripts. This book from around 1820 is one of a kind because even though the names of the magic staves are readable the explanations are coded.

In order to get what you want, or the meaning of the "Troubling stave" you would need to know two typefaces.

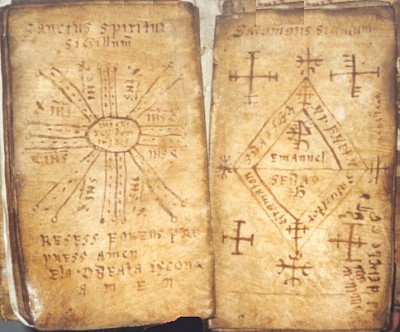

Lbs 143 8vo

In the manuscript section of the University National Library is a grimoire made of animal skin from the 17. century (Lbs. 143, 8vo) that contains a few magic staves and texts in Icelandic and Latin. Much of the text is of Christian origin, among them a letter from Christ apparently originated in Germany. Most of the staves in the manuscript are for protection.

In the pages shown there is the latter part of a Charlemagne typeface and an Aegishjalmur stave with accompanying text and the Seal of the holy spirit and the Seal of Salomon, a powerful protecting stave that has many versions.