Deities and creatures within the lore

Dieties

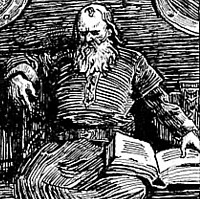

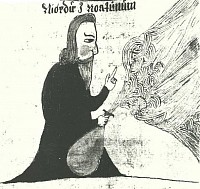

Óðinn

Odin (/ˈoʊdɪn/;[1] from Old Norse: Óðinn) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

Odin appears as a prominent god throughout the recorded history of Northern Europe, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania (from c. 2 BCE) through movement of peoples during the Migration Period (4th to 6th centuries CE) and the Viking Age (8th to 11th centuries CE). In the modern period, the rural folklore of Germanic Europe continued to acknowledge Odin. References to him appear in place names throughout regions historically inhabited by the ancient Germanic peoples, and the day of the week Wednesday bears his name in many Germanic languages, including in English.

In Old English texts, Odin holds a particular place as a euhemerized ancestral figure among royalty, and he is frequently referred to as a founding figure among various other Germanic peoples, such as the Langobards, while some Old Norse sources depict him as an enthroned ruler of the gods. Forms of his name appear frequently throughout the Germanic record, though narratives regarding Odin are mainly found in Old Norse works recorded in Iceland, primarily around the 13th century. These texts make up the bulk of modern understanding of Norse mythology.

Old Norse texts portray Odin as the son of Bestla and Borr along with two brothers, Vili and Vé, and he fathered many sons, most famously the gods Thor (with Jörð) and Baldr (with Frigg). He is known by hundreds of names. Odin is frequently portrayed as one-eyed and long-bearded, wielding a spear named Gungnir or appearing in disguise wearing a cloak and a broad hat. He is often accompanied by his animal familiars—the wolves Geri and Freki and the ravens Huginn and Muninn, who bring him information from all over Midgard—and he rides the flying, eight-legged steed Sleipnir across the sky and into the underworld. In these texts he frequently seeks greater knowledge, most famously by obtaining the Mead of Poetry, and makes wagers with his wife Frigg over his endeavors. He takes part both in the creation of the world by slaying the primordial being Ymir and in giving life to the first two humans Ask and Embla. He also provides mankind knowledge of runic writing and poetry, showing aspects of a culture hero. He has a particular association with the Yule holiday.

Odin is also associated with the divine battlefield maidens, the valkyries, and he oversees Valhalla, where he receives half of those who die in battle, the einherjar, sending the other half to the goddess Freyja's Fólkvangr. Odin consults the disembodied, herb-embalmed head of the wise Mímir, who foretells the doom of Ragnarök and urges Odin to lead the einherjar into battle before being consumed by the monstrous wolf Fenrir. In later folklore, Odin sometimes appears as a leader of the Wild Hunt, a ghostly procession of the dead through the winter sky. He is associated with charms and other forms of magic, particularly in Old English and Old Norse texts.

The figure of Odin is a frequent subject of interest in Germanic studies, and scholars have advanced numerous theories regarding his development. Some of these focus on Odin's particular relation to other figures; for example, Freyja's husband Óðr appears to be something of an etymological doublet of the god, while Odin's wife Frigg is in many ways similar to Freyja, and Odin has a particular relation to Loki. Other approaches focus on Odin's place in the historical record, exploring whether Odin derives from Proto-Indo-European mythology or developed later in Germanic society. In the modern period, Odin has inspired numerous works of poetry, music, and other cultural expressions. He is venerated with other Germanic gods in most forms of the new religious movement Heathenry; some branches focus particularly on him.

The Old Norse theonym Óðinn (runic ᚢᚦᛁᚾ on the Ribe skull fragment)[2] is a cognate of other medieval Germanic names, including Old English Wōden, Old Saxon Wōdan, Old Dutch Wuodan, and Old High German Wuotan (Old Bavarian Wûtan).[3][4][5] They all derive from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic masculine theonym *Wōðanaz (or *Wōdunaz).[3][6] Translated as 'lord of frenzy',[7] or as 'leader of the possessed',[8] *Wōðanaz stems from the Proto-Germanic adjective *wōðaz ('possessed, inspired, delirious, raging') attached to the suffix *-naz ('master of').[7]

Internal and comparative evidence all point to the ideas of a divine possession or inspiration, and an ecstatic divination.[9][10] In his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (1075–1080 AD), Adam of Bremen explicitly associates Wotan with the Latin term furor, which can be translated as 'rage', 'fury', 'madness', or 'frenzy' (Wotan id est furor : "Odin, that is, furor").[11] As of 2011, an attestation of Proto-Norse Woðinz, on the Strängnäs stone, has been accepted as probably authentic, but the name may be used as a related adjective instead meaning "with a gift for (divine) possession" (ON: øðinn).[12]

Other Germanic cognates derived from *wōðaz include Gothic woþs ('possessed'), Old Norse óðr ('mad, frantic, furious'), Old English wōd ('insane, frenzied') and Dutch woed ('frantic, wild, crazy'), along with the substantivized forms Old Norse óðr ('mind, wit, sense; song, poetry'), Old English wōþ ('sound, noise; voice, song'), Old High German wuot ('thrill, violent agitation') and Middle Dutch woet ('rage, frenzy'), from the same root as the original adjective. The Proto-Germanic terms *wōðīn ('madness, fury') and *wōðjanan ('to rage') can also be reconstructed.[3] Early epigraphic attestations of the adjective include un-wōdz ('calm one', i.e. 'not-furious'; 200 CE) and wōdu-rīde ('furious rider'; 400 CE).[10]

Philologist Jan de Vries has argued that the Old Norse deities Óðinn and Óðr were probably originally connected (as in the doublet Ullr–Ullinn), with Óðr (*wōðaz) being the elder form and the ultimate source of the name Óðinn (*wōða-naz). He further suggested that the god of rage Óðr–Óðinn stood in opposition to the god of glorious majesty Ullr–Ullinn in a similar manner to the Vedic contrast between Varuna and Mitra.[13]

The adjective *wōðaz ultimately stems from a Pre-Germanic form *uoh₂-tós, which is related to the Proto-Celtic terms *wātis, meaning 'seer, sooth-sayer' (cf. Gaulish wāteis, Old Irish fáith 'prophet') and *wātus, meaning 'prophesy, poetic inspiration' (cf. Old Irish fáth 'prophetic wisdom, maxims', Old Welsh guaut 'prophetic verse, panegyric').[9][10][14] According to some scholars, the Latin term vātēs ('prophet, seer') is probably a Celtic loanword from the Gaulish language, making *uoh₂-tós ~ *ueh₂-tus ('god-inspired') a shared religious term common to Germanic and Celtic rather than an inherited word of earlier Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin.[9][10] In the case a borrowing scenario is excluded, a PIE etymon *(H)ueh₂-tis ('prophet, seer') can also be posited as the common ancestor of the attested Germanic, Celtic and Latin forms.[6]

More than 170 names are recorded for Odin; the names are variously descriptive of attributes of the god, refer to myths involving him, or refer to religious practices associated with him. This multitude makes Odin the god with the most known names among the Germanic peoples.[15] Professor Steve Martin has pointed out that the name Odinsberg (Ounesberry, Ounsberry, Othenburgh)[16] in Cleveland Yorkshire, now corrupted to Roseberry (Topping), may derive from the time of the Anglian settlements, with nearby Newton under Roseberry and Great Ayton[17] having Anglo Saxon suffixes. The very dramatic rocky peak was an obvious place for divine association, and may have replaced Bronze Age/Iron Age beliefs of divinity there, given that a hoard of bronze votive axes and other objects was buried by the summit.[18][19] It could be a rare example, then, of Nordic-Germanic theology displacing earlier Celtic mythology in an imposing place of tribal prominence.

In his opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, Richard Wagner refers to the god as Wotan, a spelling of his own invention which combines the Old High German Wuotan with the Low German Wodan.[20

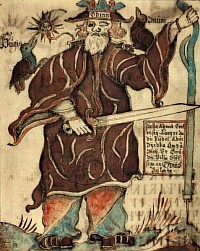

Þórr

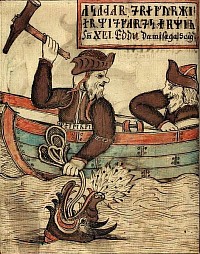

Thor’Thor (from Old Norse: Þórr) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and fertility. Besides Old Norse Þórr, the deity occurs in Old English as Þunor, in Old Frisian as Thuner, in Old Saxon as Thunar, and in Old High German as Donar, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Þun(a)raz, meaning 'Thunder'.

Thor is a prominently mentioned god throughout the recorded history of the Germanic peoples, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania, to the Germanic expansions of the Migration Period, to his high popularity during the Viking Age, when, in the face of the process of the Christianization of Scandinavia, emblems of his hammer, Mjölnir, were worn and Norse pagan personal names containing the name of the god bear witness to his popularity.

Due to the nature of the Germanic corpus, narratives featuring Thor are only attested in Old Norse, where Thor appears throughout Norse mythology. Norse mythology, largely recorded in Iceland from traditional material stemming from Scandinavia, provides numerous tales featuring the god. In these sources, Thor bears at least fifteen names, is the husband of the golden-haired goddess Sif, is the lover of the jötunn Járnsaxa. With Sif, Thor fathered the goddess (and possible valkyrie) Þrúðr; with Járnsaxa, he fathered Magni; with a mother whose name is not recorded, he fathered Móði, and he is the stepfather of the god Ullr. Thor is the son of Odin and Jörð,[1] by way of his father Odin, he has numerous brothers, including Baldr. Thor has two servants, Þjálfi and Röskva, rides in a cart or chariot pulled by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr (that he eats and resurrects), and is ascribed three dwellings (Bilskirnir, Þrúðheimr, and Þrúðvangr). Thor wields the hammer Mjölnir, wears the belt Megingjörð and the iron gloves Járngreipr, and owns the staff Gríðarvölr. Thor's exploits, including his relentless slaughter of his foes and fierce battles with the monstrous serpent Jörmungandr—and their foretold mutual deaths during the events of Ragnarök—are recorded throughout sources for Norse mythology.

Into the modern period, Thor continued to be acknowledged in rural folklore throughout Germanic-speaking Europe. Thor is frequently referred to in place names, the day of the week Thursday bears his name (modern English Thursday derives from Old English þunresdæġ, 'Þunor's day'), and names stemming from the pagan period containing his own continue to be used today, particularly in Scandinavia. Thor has inspired numerous works of art and references to Thor appear in modern popular culture. Like other Germanic deities, veneration of Thor is revived in the modern period in Heathenry.o

The Old Norse theonym Þórr (older poetic Þunarr) goes back to an earlier Proto-Norse form reconstructed as Þunraʀ.[2] It is a cognate (linguistic sibling of the same origin) of the medieval Germanic forms Donar (Old High German), Þunor (Old English), Thuner (Old Frisian), and Thunar (Old Saxon).[3] They descend from the Proto-Germanic reconstructed theonym *Þun(a)raz ('Thunder'),[4] which is identical to the name of the ancient Celtic god Taranus (by metathesis–switch of sounds–of an earlier *Tonaros, attested in the dative tanaro and the Gaulish river name Tanarus), and further related to the Latin epithet Tonans (attached to Jupiter), via the common Proto-Indo-European root for 'thunder' *(s)tenh₂-.[5] According to scholar Peter Jackson, those theonyms may have emerged as the result of the fossilization of an original epithet (or epiclesis, i.e. invocational name) of the Proto-Indo-European thunder-god *Perkwunos, since the Vedic weather-god Parjanya is also called stanayitnú- ('Thunderer').[6]

The perfect match between the thunder-gods *Tonaros and *Þun(a)raz, which both go back to a common form *ton(a)ros ~ *tṇros, is notable in the context of early Celtic–Germanic linguistic contacts, especially when added to other inherited terms with thunder attributes, such as *Meldunjaz–*meldo- (from *meldh- 'lightning, hammer', i.e. *Perkwunos' weapon) and *Fergunja–*Fercunyā (from *perkwun-iyā 'wooded mountains', i.e. *Perkwunos' realm).[7]

The English weekday name Thursday comes from Old English Þunresdæg, meaning 'day of Þunor'. It is cognate with Old Norse Þórsdagr and with Old High German Donarestag. All of these terms derive from the Late Proto-Germanic weekday *Þonaresdag ('Day of *Þun(a)raz'), a calque of Latin Iovis dies ('Day of Jove'; cf. modern Italian giovedì, French jeudi, Spanish jueves). By employing a practice known as interpretatio germanica during the Roman period, ancient Germanic peoples adopted the Latin weekly calendar and replaced the names of Roman gods with their own.[8]

Beginning in the Viking Age, personal names containing the theonym Thórr are recorded with great frequency, whereas no examples are known prior to this period. Thórr-based names may have flourished during the Viking Age as a defiant response to attempts at Christianization, similar to the wide scale Viking Age practice of wearing Thor's hammer pendants.[9]

Heimdallr

In Norse mythology, Heimdall (from Old Norse Heimdallr) is a god. He is the son of Odin and nine mothers. Heimdall keeps watch for invaders and the onset of Ragnarök from his dwelling Himinbjörg, where the burning rainbow bridge Bifröst meets the sky. He is attested as possessing foreknowledge and keen senses, particularly eyesight and hearing. The god and his possessions are described in enigmatic manners. For example, Heimdall is emerald-toothed, "the head is called his sword," and he is "the whitest of the gods."

Heimdall possesses the resounding horn Gjallarhorn and the golden-maned horse Gulltoppr, along with a store of mead at his dwelling. He is the son of Nine Mothers, and he is said to be the originator of social classes among humanity. Other notable stories include the recovery of Freyja's treasured possession Brísingamen while doing battle in the shape of a seal with Loki. The antagonistic relationship between Heimdall and Loki is notable, as they are foretold to kill one another during the events of Ragnarök. Heimdallr is also known as Rig, Hallinskiði, Gullintanni, and Vindlér or Vindhlér.

Heimdall is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material; in the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, both written in the 13th century; in the poetry of skalds; and on an Old Norse runic inscription found in England. Two lines of an otherwise lost poem about the god, Heimdalargaldr, survive. Due to the enigmatic nature of these attestations, scholars have produced various theories about the nature of the god, including his relation to sheep, borders, and waves.

The etymology of the name is obscure, but 'the one who illuminates the world' has been proposed. Heimdallr may be connected to Mardöll, one of Freyja's names.[1] Heimdallr and its variants are usually anglicized as Heimdall (/ˈheɪmdɑːl/;[2] with the nominative -r dropped).

Heimdall is attested as having three other names; Hallinskiði, Gullintanni, and Vindlér or Vindhlér. The name Hallinskiði is obscure, but has resulted in a series of attempts at deciphering it. Gullintanni literally means 'the one with the golden teeth'. Vindlér (or Vindhlér) translates as either 'the one protecting against the wind' or 'wind-sea'. All three have resulted in numerous theories about the god.[3]

Baldr

Baldr (also Balder, Baldur) is a god in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, Baldr (Old Norse: [ˈbɑldz̠]) is a son of the god Odin and the goddess Frigg, and has numerous brothers, such as Thor and Váli. In wider Germanic mythology, the god was known in Old English as Bældæġ, and in Old High German as Balder, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Balðraz ('hero' or 'prince').

During the 12th century, Danish accounts by Saxo Grammaticus and other Danish Latin chroniclers recorded a euhemerized account of his story. Compiled in Iceland during the 13th century, but based on older Old Norse poetry, the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda contain numerous references to the death of Baldr as both a great tragedy to the Æsir and a harbinger of Ragnarök.

According to Gylfaginning, a book of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda, Baldr's wife is Nanna and their son is Forseti. Baldr had the greatest ship ever built, Hringhorni, and there is no place more beautiful than his hall, Breidablik

The Old Norse theonym Baldr ('brave, defiant'; also 'lord, prince') and its various Germanic cognates – including Old English Bældæg and Old High German Balder (or Palter) – probably stems from Proto-Germanic *Balðraz ('Hero, Prince'; cf. Old Norse mann-baldr 'great man', Old English bealdor 'prince, hero'), itself a derivative of *balþaz, meaning 'brave' (cf. Old Norse ballr 'hard, stubborn', Gothic balþa* 'bold, frank', Old English beald 'bold, brave, confident', Old Saxon bald 'valiant, bold', Old High German bald 'brave, courageous').[1][2]

This etymology was originally proposed by Jacob Grimm (1835),[3] who also speculated on a comparison with the Lithuanian báltas ('white', also the name of a light-god) based on the semantic development from 'white' to 'shining' then 'strong'.[1][2] According to linguist Vladimir Orel, this could be linguistically tenable.[2] Philologist Rudolf Simek also argues that the Old English Bældæg should be interpreted as meaning 'shining day', from a Proto-Germanic root *bēl- (cf. Old English bæl, Old Norse bál 'fire')[4] attached to dæg ('day').[5]

Old Norse also shows the usage of the word as an honorific in a few cases, as in baldur î brynju (Sæm. 272b) and herbaldr (Sæm. 218b), in general epithets of heroes. In continental Saxon and Anglo-Saxon tradition, the son of Woden is called not Bealdor but Baldag (Saxon) and Bældæg, Beldeg (Anglo-Saxon), which shows association with "day", possibly with Day personified as a deity. This, as Grimm points out, would agree with the meaning "shining one, white one, a god" derived from the meaning of Baltic baltas, further adducing Slavic Belobog and German Berhta.[6]

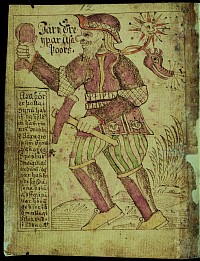

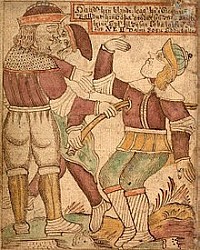

Loki

Loki is a god in Norse mythology. According to some sources, Loki is the son of Fárbauti (a jötunn) and Laufey (mentioned as a goddess), and the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. Loki is married to Sigyn and they have two sons, Narfi or Nari and Váli. By the jötunn Angrboða, Loki is the father of Hel, the wolf Fenrir, and the world serpent Jörmungandr. In the form of a mare, Loki was impregnated by the stallion Svaðilfari and gave birth to the eight-legged horse Sleipnir.

Loki's relation with the gods varies by source; he sometimes assists the gods and sometimes behaves maliciously towards them. Loki is a shape shifter and in separate incidents appears in the form of a salmon, a mare, a fly, and possibly an elderly woman named Þökk (Old Norse 'thanks'). Loki's positive relations with the gods end with his role in engineering the death of the god Baldr, and eventually, Odin's specially engendered son Váli binds Loki with the entrails of one of his sons; in the Prose Edda, this son, Nari or Narfi, is killed by another son of Loki who is also called Váli. In both the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, the goddess Skaði is responsible for placing a serpent above him while he is bound. The serpent drips venom from above him that Sigyn collects into a bowl; however, she must empty the bowl when it is full, and the venom that drips in the meantime causes Loki to writhe in pain, thereby causing earthquakes. With the onset of Ragnarök, Loki is foretold to slip free from his bonds and to fight against the gods among the forces of the jötnar, at which time he will encounter the god Heimdallr, and the two will slay each other.

Loki is referred to in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; the Norwegian Rune Poems, in the poetry of skalds, and in Scandinavian folklore. Loki may be depicted on the Snaptun Stone, the Kirkby Stephen Stone, and the Gosforth Cross. Scholars have debated Loki's origins and role in Norse mythology, which some have described as that of a trickster god. Loki has been depicted in or referenced in a variety of media in modern popular culture.

The etymology of the name Loki has been extensively debated. The name has at times been associated with the Old Norse word logi ('flame'), but there seems not to be a sound linguistic basis for this. Rather, the later Scandinavian variants of the name (such as Faroese Lokki, Danish Lokkemand, Norwegian Loke and Lokke, Swedish Luki and Luku) point to an origin in the Germanic root *luk-, which denoted things to do with loops (like knots, hooks, closed-off rooms, and locks). This corresponds with usages such as the Swedish lockanät and Faroese lokkanet ('cobweb', literally 'Lokke's web') and Faroese lokki~grindalokki~grindalokkur, 'daddy-long-legs' referring both to crane flies and harvestmen, modern Swedish lockespindlar ("Locke-spiders"). Some Eastern Swedish traditions referring to the same figure use forms in n- like Nokk(e), but this corresponds to the *luk- etymology insofar as those dialects consistently used a different root, Germanic *hnuk-, in contexts where western varieties used *luk-: "nokke corresponds to nøkkel" ('key' in Eastern Scandinavian) "as loki~lokke to lykil" ('key' in Western Scandinavian).[1]

While it has been suggested that this association with closing could point to Loki's apocalyptic role at Ragnarök,[2] "there is quite a bit of evidence that Loki in premodern society was thought to be the causer of knots/tangles/loops, or himself a knot/tangle/loop. Hence, it is natural that Loki is the inventor of the fishnet, which consists of loops and knots, and that the word loki (lokke, lokki, loke, luki) is a term for makers of cobwebs: spiders and the like."[3] Though not prominent in the oldest sources, this identity as a "tangler" may be the etymological meaning of Loki's name.

In various poems from the Poetic Edda (stanza 2 of Lokasenna, stanza 41 of Hyndluljóð, and stanza 26 of Fjölsvinnsmál), and sections of the Prose Edda (chapter 32 of Gylfaginning, stanza 8 of Haustlöng, and stanza 1 of Þórsdrápa) Loki is alternatively referred to as Loptr, which is generally considered derived from Old Norse lopt meaning "air", and therefore points to an association with the air.[4]

The name Hveðrungr (Old Norse '?roarer') is also used in reference to Loki, occurring in names for Hel (such as in Ynglingatal, where she is called hveðrungs mær) and in reference to Fenrir (as in Völuspa).[5]

Freyr

Freyr (Old Norse: ‘Lord’), sometimes anglicized as Frey, is a widely attested god in Norse mythology, associated with kingship, fertility, peace, prosperity, fair weather, and good harvest. Freyr, sometimes referred to as Yngvi-Freyr, was especially associated with Sweden and seen as an ancestor of the Swedish royal house. According to Adam of Bremen, Freyr was associated with peace and pleasure, and was represented with a phallic statue in the Temple at Uppsala. According to Snorri Sturluson, Freyr was "the most renowned of the æsir", and was venerated for good harvest and peace.

In the mythological stories in the Icelandic books the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, Freyr is presented as one of the Vanir, the son of the god Njörðr and his sister-wife, as well as the twin brother of the goddess Freyja. The gods gave him Álfheimr, the realm of the Elves, as a teething present. He rides the shining dwarf-made boar Gullinbursti, and possesses the ship Skíðblaðnir, which always has a favorable breeze and can be folded together and carried in a pouch when it is not being used. Freyr is also known to have been associated with the horse cult. He also kept sacred horses in his sanctuary at Trondheim in Norway.[2] He has the servants Skírnir, Byggvir and Beyla.

The most extensive surviving Freyr myth relates Freyr's falling in love with the female jötunn Gerðr. Eventually, she becomes his wife but first Freyr has to give away his sword, which fights on its own "if wise be he who wields it." Although deprived of this weapon, Freyr defeats the jötunn Beli with an antler. However, lacking his sword, Freyr will be killed by the fire jötunn Surtr during the events of Ragnarök.

Like other Germanic deities, veneration of Freyr was revived during the modern period through the Heathenry movement.

The Old Norse name Freyr ('lord') is generally thought to descend from a Proto-Norse form reconstructed as *frawjaʀ, stemming from the Proto-Germanic noun *frawjaz ~ *fraw(j)ōn ('lord'), and cognate with Gothic frauja, Old English frēa, or Old High German frō, all meaning 'lord, master'.[3][4] The runic form frohila, derived from an earlier *frōjila, may also be related.[3] Recently, however, an etymology deriving the name of the god from a nominalized form of the Proto-Scandinavian adjective *fraiw(i)a- ('fruitful, generative') has also been proposed.[5][6] According to linguist Guus Kroonen, "within Germanic, the attestation of ON frjar, frjór, frær, Icel. frjór adj. 'fertile; prolific' < *fraiwa- clearly seems to point to a stem *frai(w)- meaning 'fecund'. Both in form and meaning, fraiwa- ('seed') is reminiscent of Freyr 'fertility deity' < *frauja-. We may therefore consider the possibility that *fraiwa- was metathesized from *frawja-, a collective of some kind."[7] Freyr is also known by a series of other names which describe his attributes and role in religious practice and associated mythology.

Freyja

In Norse paganism, Freyja (Old Norse "(the) Lady") is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr (magic for seeing and influencing the future). Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chariot pulled by two cats, is accompanied by the boar Hildisvíni, and possesses a cloak of falcon feathers. By her husband Óðr, she is the mother of two daughters, Hnoss and Gersemi. Along with her twin brother Freyr, her father Njörðr, and her mother (Njörðr's sister, unnamed in sources), she is a member of the Vanir. Stemming from Old Norse Freyja, modern forms of the name include Freya, Freyia, and Freja.

Freyja rules over her heavenly field, Fólkvangr, where she receives half of those who die in battle. The other half go to the god Odin's hall, Valhalla. Within Fólkvangr lies her hall, Sessrúmnir. Freyja assists other deities by allowing them to use her feathered cloak, is invoked in matters of fertility and love, and is frequently sought after by powerful jötnar who wish to make her their wife. Freyja's husband, the god Óðr, is frequently absent. She cries tears of red gold for him, and searches for him under assumed names. Freyja has numerous names, including Gefn, Hörn, Mardöll, Sýr, Vanadís, and Valfreyja.

Freyja is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; in the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, composed by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century; in several Sagas of Icelanders; in the short story "Sörla þáttr"; in the poetry of skalds; and into the modern age in Scandinavian folklore.

Scholars have debated whether Freyja and the goddess Frigg ultimately stem from a single goddess common among the Germanic peoples. They have connected her to the valkyries, female battlefield choosers of the slain, and analyzed her relation to other goddesses and figures in Germanic mythology, including the thrice-burnt and thrice-reborn Gullveig/Heiðr, the goddesses Gefjon, Skaði, Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa, Menglöð, and the 1st century CE "Isis" of the Suebi. In Scandinavia, Freyja's name frequently appears in the names of plants, especially in southern Sweden. Various plants in Scandinavia once bore her name, but it was replaced with the name of the Virgin Mary during the process of Christianization. Rural Scandinavians continued to acknowledge Freyja as a supernatural figure into the 19th century, and Freyja has inspired various works of art.

The name Freyja transparently means 'lady, mistress' in Old Norse.[1] Stemming from the Proto-Germanic feminine noun *frawjōn ('lady, mistress'), it is cognate with Old Saxon frūa ('lady, mistress') or Old High German frouwa ('lady'; cf. modern German Frau). Freyja is also etymologically close to the name of the god Freyr, meaning 'lord' in Old Norse.[2][3] The theonym Freyja is thus considered to have been an epithet in origin, replacing a personal name that is now unattested.[4]

In addition to Freyja, Old Norse sources refer to the goddess by the following names:

Gef, Hörn, Mardöll, Skjálf, Sýr, Thröng, Thrungva, Valfreyja and Vanadís.

Ægir

Ægir (anglicised as Aegir; Old Norse 'sea'), Hlér (Old Norse 'sea'), or Gymir (Old Norse less clearly 'sea, engulfer'), is a jötunn and a personification of the sea in Norse mythology. In the Old Norse record, Ægir hosts the gods in his halls and is associated with brewing ale. Ægir is attested as married to a goddess, Rán, who also personifies the sea, and together the two produced daughters who personify waves, the Nine Daughters of Ægir and Rán, and Ægir's son is Snær, personified snow. Ægir may also be the father of the beautiful jötunn Gerðr, wife of the god Freyr, or these may be two separate figures who share the same name (see below and Gymir (father of Gerðr)).

One of Ægir's names, Hlér, is the namesake of the island Læsø (Old Norse Hléysey 'Hlér's island') and perhaps also Lejre in Denmark. Scholars have long analyzed Ægir's role in the Old Norse corpus, and the concept of the figure has had some influence in modern popular culture.

The Old Norse name Ægir ('sea') may stem from a Proto-Germanic form *āgwi-jaz ('that of the river/water'),[1] itself a derivative of the stem *ahwō- ('river'; cf. Gothic aƕa 'body of water, river', Old English ēa 'stream', Old High German aha 'river').[2] Richard Cleasby and Guðbrandur Vigfússon saw his name as deriving from an ancient Indo-European root.[3] Linguist Guus Kroonen argues that the Germanic stem *ahwō- is probably of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin, as it may be cognate with Latin aqua (via a common form *h₂ekʷ-eh₂-), and ultimately descend from the PIE root *h₂ep- ('water'; cf. Sanskrit áp- 'water', Tocharian āp- 'water, river').[2] Linguist Michiel de Vaan notes that the connection between Proto-Germanic *ahwō- and Old Norse Ægir remains uncertain, and that *ahwō- and aqua, if cognates, may also be loanwords from a non-Indo-European language.[4]

The name Ægir is identical to a noun for 'sea' in skaldic poetry, itself a base word in many kennings. For instance, a ship is described as "Ægir's horse" and the waves as the "daughters of Ægir".[5]

Poetic kennings in both Hversu Noregr byggðist (How Norway Was Settled) and Skáldskaparmál (The Language of Poetry) treat Ægir and the sea-jötunn Hlér, who lives on the Hlésey ('Hlér island', modern Læsø), as the same figure.[6][7][8]

The meaning of the Old Norse name Gymir is unclear.[9][10] Proposed translations include 'the earthly' (from Old Norse gumi), 'the wintry one' (from gemla), or 'the protector', the 'engulfer' (from geyma).[9][10][11]

Njörðr

In Norse mythology, Njörðr (Old Norse: Njǫrðr) is a god among the Vanir. Njörðr, father of the deities Freyr and Freyja by his unnamed sister, was in an ill-fated marriage with the goddess Skaði, lives in Nóatún and is associated with the sea, seafaring, wind, fishing, wealth, and crop fertility.

Njörðr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, in euhemerized form as a beloved mythological early king of Sweden in Heimskringla, also written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, as one of three gods invoked in the 14th century Hauksbók ring oath, and in numerous Scandinavian place names. Veneration of Njörðr survived into the 18th or 19th century Norwegian folk practice, where the god is recorded as Njor and thanked for a bountiful catch of fish.

Njörðr has been the subject of an amount of scholarly discourse and theory, often connecting him with the figure of the much earlier attested Germanic goddess Nerthus, the hero Hadingus, and theorizing on his formerly more prominent place in Norse paganism due to the appearance of his name in numerous place names. Njörðr is sometimes modernly anglicized as Njord, Njoerd, or Njorth.

The name Njörðr corresponds to that of the older Germanic fertility goddess Nerthus (early 1st c. AD). Both derive from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Nerþuz.[1][2]

The original meaning of the name is contested, but it may be related to the Irish word nert which means "force" and "power". It has been suggested that the change of sex from the female Nerthus to the male Njörðr is due to the fact that feminine nouns with u-stems disappeared early in Germanic language while the masculine nouns with u-stems prevailed. However, other scholars hold the change to be based not on grammatical gender but on the evolution of religious beliefs; that *Nerþuz and Njörðr appear as different genders because they are to be considered separate beings.[3] The name Njörðr may be related to the name of the Norse goddess Njörun.[4]

Njörðr's name appears in various place names in Scandinavia, such as Nærdhæwi (now Nalavi, Närke), Njærdhavi (now Mjärdevi, Linköping; both using the religious term vé), Nærdhælunda (now Närlunda, Helsingborg), Nierdhatunum (now Närtuna, Uppland) in Sweden,[3] Njarðvík in southwest Iceland, Njarðarlög and Njarðey (now Nærøy) in Norway.[5] Njörðr's name appears in a word for sponge; Njarðarvöttr (Old Norse: Njarðarvǫttr, "Njörðr's glove"). Additionally, in Old Icelandic translations of Classical mythology the Roman god Saturn's name is glossed as "Njörðr."[5]

Creatures

Hafgufa

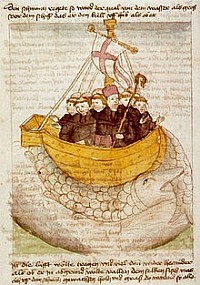

Hafgufa (Old Norse: haf "sea" + Old Norse: gufa "steam";[2][3] "sea-reek";[a][5] "sea-steamer"[6]) is a sea creature, purported to inhabit Iceland's waters (Greenland Sea) and southward towards Helluland. Although it was thought to be a sea monster, research suggests that the stories originated from a specialised feeding technique among whales known as trap-feeding.[7][8]

The hafgufa is mentioned in the mid-13th century Norwegian tract called the Konungs skuggsjá ("King's Mirror"). Later recensions of Örvar-Odds saga feature hafgufa and lyngbakr as similar but distinct creatures.

According to the Norwegian didactic work, this creature uses its own vomit like chumming bait to gather prey fish. In the Fornaldarsaga, the hafgufa is reputed to consume even whales or ships and men, though Oddr's ship merely sailed through its jaws above water, which appeared to be nothing more than rocks.

This creature's name appears as hafgufa in Old Norse in the 13th century Norwegian work.[9][b][10]

In the Snorra Edda, the hafgufa ("sea-steamer"[6]) appears in the list (þulur) of whales.[11][12] The spelling is also hafgúa in some copies.[13] An 18th century source glosses the term margúa 'mermaid' as hafgúa.[c][14]

This was rendered "hafgufa ('[mermaid]')" in a recent excerpt of this work,[15] but has been translated 'kraken' in the past.[16] It was translated as "sea-reek"[5] in the saga.[18]

In the Speculum regale (aka Konungs skuggsjá, the "King's Mirror"), an Old Norwegian philosophical didactic work written in the mid-13th century, the King told his son[19][20] of several whales that inhabit the Icelandic seas, concluding with a description of a large whale that he himself feared, but he doubted anyone would believe him about without seeing it. He described the hafgufa as a massive fish that looked more like an island than like a living thing. The King noted that hafgufa was rarely seen, but always seen in the same two places. He concluded there must be only two of them and that they must be infertile, otherwise the seas would be full of them.[15]

The King described the feeding manner of hafgufa: The fish would belch, which would expel so much food that it would attract all the nearby fish. Once a large number had crowded into its mouth and belly, it would close its mouth and devour them all at once.[15][d]

Its mention in the Speculum regale was noted by Olaus Wormiaus (Ole Worm) in his posthumous Museum Wormianum (1654)[21][22] and by another Dane, Thomas Bartholin the senior (1657).[1] Ole Worm classed it as the 22nd type of Cetus, as did Bartholin, but one difference was that Ole Worm's book printed the entry with the skewed spelling hafgufe.[22][1]

In the later version of Örvar-Odds saga[23] dating to the late 14th century,[24] hafgufa is described as the largest sea monster (sjóskrímsl) of all,[e] which fed on whales, ships, men, and anything it could catch, according to the deck officer Vignir Oddsson who knew the lore.[5][26] He said it lived underwater, but reared its snout ("mouth and nostrils") above water for a duration until the tide changed, and that it was the nostril and lower jaw which they had sailed in-between, although they mistook these for two massive rocks rising from the sea.[25][27][5][f]

Örvar-Oddr and his crew, who started from the Greenland Sea were sailing along the coast south and westward, towards a fjord called Skuggi[g][28] on Helluland (also given by the English-translated name of "Slabland"), and it is on the way there that they encountered two monsters, the hafgufa ('sea-reek') and lyngbakr ('heather-back').[5]

The aspidochelone of the Physiologus is identified as the potential source for the hafgufa lore.[29]

Although the original aspidochelone was a turtle-island of warmer waters, this was reinvented as a type of whale named aspedo in the Icelandic Physiologus (fragment B, No. 8).[29][30][h] In the Icelandic aspedo was described as a whale (hvalr) being mistaken for an island,[33][34] and as opening its mouth to issue a perfume of sorts to attract prey.[35] Halldór Hermannsson [is] observed that these were represented as two distinct illustrations in the Icelandic copy; he further theorized that this led to the mistaken notion of separate creatures called hafgufa and lyngbakr in existence, as occurs in the saga.[23][26]

Contrary to the saga, Danish physician Thomas Bartholin in his Historiarum anatomicarum IV (1657) stated that the hafgufa ('sea vapor') was synonymous with 'lyngbak' ([sic.], 'back like Erica plants').[i] He added that it was on the back of this beast that St. Brendan read his Mass, causing the island to sink after their departure.[1][37] The Icelander Jón Guðmundsson (d. 1658)'s Natural History of Iceland[j] also equated the lyngbakr and hafgufa with the beast mistaken for an island in St. Brendan's voyage.[38] The island-like creature is indeed told of in the legend of Brendan's voyage,[39] though the giant fish is named Jasconius/Jaskonius.[40][41][42]

Hans Egede writing on the kracken (kraken) of Norway equates it with the Icelandic hafgufa, though has heard little on the latter.[43] and later, the non-native Moravian cleric David Crantz [de]'s History of Greenland (1765, in German) treated hafgafa as synonymous with the krake[n] in the Norwegian tongue.[44][45] However, Finnur Jónsson for instance has expressed skepticism towards the notion which developed that the krake had its origins in the hafgufa.[46]

In 2023, scientists reported observed behaviour of whales resembling that of the Hafgufa of legends, by staying stationary on the sea surface with their jaws open and waiting for fish to swim into mouths. The whale may also use chewed up fish to attract more fish. The scientists noted that the earliest description of Hafgufa described it as a type of whale, and proposed that this behaviour of whale as the origin of the Hafgufa myth which became more fantastic in later centuries.[8][47]

Lindormr

The lindworm (worm meaning snake), also spelled lindwyrm or lindwurm, is a mythical creature in Northern and Central European folklore living deep in the forest that traditionally has the shape of a giant serpent monster. It can be seen as a sort of dragon.

According to legend, everything that lies under the lindworm will increase as the lindworm grows, giving rise to tales of dragons that brood over treasures to become richer. Legend tells of two kinds of lindworm, a good one associated with luck, often a cursed prince who has been transformed into another beast (as in the fairy tale The Frog Prince), and a bad one, a dangerous man-eater which will attack humans on sight. A lindworm may swallow its own tail, turning itself into a rolling wheel, as a method of pursuing fleeing humans.[1]

The head of the 16th-century lindworm statue at Lindwurm Fountain (Lindwurmbrunnen [de]) in Klagenfurt, Austria, is modeled on the skull of a woolly rhinoceros found in a nearby quarry in 1335. It has been cited as the earliest reconstruction of an extinct animal.[2][3][4]

Lindworm derives from Old High German lint and orm, perhaps from the Proto-Germanic adjective *linþia- meaning "flexible", or perhaps by way of Old Danish/Old Saxon lithi, Old High German lindi, "soft, mild" (German lind, (ge)linde), Old English liðe (English lithe, "agile"). The term occurs in Middle High German as lintwurm and was adopted from German into Scandinavia as Old Swedish lindormber (modern Swedish lindorm), Danish lindorm, meaning "lind-snake".[5] In Icelandic, the term linnormr was used to translate German sources to produce Þiðreks saga (an Old Norse chivalric saga adapted from the Continent from the late 13th c.)[6][7]

Swedish lindworm (lindorm)[edit]

In Swedish folklore, lindworms traditionally appear as giant forest serpents without limbs, living between the rocks deep in the forest. They are said to be dark in color with a brighter underside. Along the spine it has fish like dorsal fins or horse like mane, sometimes being called a "mane snake" (Swedish: manorm). For defence and attack it can spit out a foul milk-like substance which can blind enemies.[1]

Lindworm eggs are laid under the bark of Tilia cordata trees (Swedish: Lind, thereof the name) and once hatched they slither away and make a home in some pile of rocks.[1] When fully grown they can become extremely long. To counter this during hunting they swallow their own tail to become a wheel, after which they roll at extremely high speeds to pursue prey. This has given them the nickname wheel snake (Swedish: hjulorm).[1]

Late belief in lindworms in Sweden[edit]

The belief in the reality of a lindorm, a giant limbless serpent, persisted well into the 19th century in some parts. The Swedish folklorist Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius (1818–1889) collected in the mid 19th century stories of legendary creatures in Sweden and met several people in Småland, Sweden who said they had encountered giant snakes, sometimes equipped with a long mane. He gathered around 50 eyewitness reports, and in 1884 offered a cash reward for a captured specimen, dead or alive.[8] Hyltén-Cavallius came to be ridiculed by Swedish scholars and as no one ever managed to claim the reward it resulted in a cryptozoological defeat. Rumours of the existence of lindworms in Småland soon abated.[9][10]

In Central Europe the lindworm usually resembles a dragon or similar. It generally appears with a scaly serpentine body, dragon's head and two clawed forelimbs, sometimes also with wings. Some examples, such as the 16th-century lindworm statue at Lindwurm Fountain in Klagenfurt, Austria, has four limbs and two wings.

Most limbed depictions imply lindworms do not walk on their two limbs like a wyvern, but move like a mole lizard: they slither like a snake and use their arms for traction.[11]

There exist several related offshoots of the winged lindworm outside Northern and Central Europe, such as the French guivre and vouivre, and to some extent the British wyvern. The French guivre and vouivre are more dragon-like than the traditional lindworms while the British wyvern is a full-fledged dragon canonically.