Holidays and traditions

The Old Norse Calender

To begin, the Nordic year was generally divided into two equal parts; sumar (summer) and vetur (winter). Each “big” part had six months, and they worked from a lunar calendar rather than having fixed dates.

The months of vetur were; gormánuður, ýlir, mörsugur, Þorri, góa and einmánuður.

The months of sumar were; harpa, skerpla, sólmánuður, heyannir, tvímánuður and haustmánuður.

So there were 12 months, just like today, but they were offset by about two weeks. In addition to this, they had a name for both the darkest days of the year - skammdegí - and the lightest - nóttleysa ('nightlessness').

Note that some names here are Icelandic or Swedish in order to indicate the general idea or purpose of a given month or celebration. Regions did differ in names or timing.

VETR – Winter Months

Gormánuður (Slaughter Month - October 14th - November 13th)

Also: vetr ("winter"); gormanoðr/gormánuðr/gormánaðr ("slaughtering month") The first month of winter. The winter feast (during Veturnettr or Winternights, was Haustblót, or in some regions Disablót) and it was held on the first day of this month, determined by the first full moon in that time range. The feast is dedicated to Freyr and is a harvest celebration.

Typically, and according to Víga-Glúms saga, Disablót was celebrated. It was a welcome to winter and offerings for a good year were made. Volva would read spiritual signs to predict the harshness of winter and answer questions of fate. Utiseta (sitting out) was also a common practice at this time.

Alvablót, or Alfblót, was a feast in honor of your ancestors and the Alfar (elves), held on the 7th of November. This was a private affair, for the closest family only.

Ýlir (Jol Month - November 14th - December 13th) Also: ylir ("yule"), frermánuðr/frermánaðr ("frost month”). This is the second month of winter. It is also most likely one of the many “kennings” or names for Odin: Jólnir. The celebration of Jól is still debated, in that the duration of the celebration probably varied region to region. Some places might just celebrate the solstice, but others would celebrate for 12 or 14 days, and others from the solstice until Hoggunótt (January 12th).

In addition to a large family feast, a common practice was drinking and toasting the gods, land spirits, and loved ones both alive and passed. In some places Odin was honored, but in others Thor, Njörðr, Freyr and many goddesses were honored.

Some Nordic cultures also did an Åregang, where you walk and mark out the borders of your property, at night and with candles or torches.

Mörsugur (December 14th - January 12th) Also: mörsugr ("fat sucker"); jólmanoðr ("yule month"); hrutmánuðr/hrutmánaðr ("ram month") Mörsugur is the third month of winter. New Years’ Eve was also commonly celebrated, giving tribute again to the land-spirits and ancestors. Around January 12th at Midwinter Day, some may celebrate a midwinterblót also called Hoggunótt to welcome back the sun.

Þorri - January 13th - February 11th Also: þorri (possibly related to the god Þórr); but Þorri is the fourth winter month. This is the month to celebrate Þorrablót. Customarily, one honored the father or elder man of the house with a feast or gifts, rather like a “Father’s Day” in modern times. Modern times, Þorrablót is held the first Friday after January 19th.

Gói - February 12th - March 13th. Gói is the fifth winter month and the women's month, rather like the modern “Mother’s Day” but specifically for men to celebrate and appreciate their wives. Cakes, flowers, and coffee were common gifts. Gói is specifically from West Norse tradition, and said to be the daughter of Þorri.

Einmánuður - March 14th - April 13th. This is the last month of winter and the name just means “One Month”. Around March 21st is the Vernal Equinox, and it's customary to have a feast to celebrate fertility. Einmánuður is also a celebration for young boys and young men.

SUMAR - Summer

Harpa (April 14th - May 13th). On the first day of summer, a great sacrifical feast is held - the summer blót. This is for victory in battle and good luck in travel. Harpa is the month for young girls just like Einmánuður is the month for boys - in the same way that Þorri and Gói are dedicated to adult men and women.

Skerpla - May 14th - June 12th. Skerpla is the second summer month. Small local celebrations for “Moving Days” were around Jun 4-7, and for the “Longest Day” around June 20. Typically, “moving days” refer to a time when the contracts of hired farm hands were either renewed or ended, and workers moved to different farms for work.

Sólmánuður - June 13th - July 12th. This is the third month of summer. Sólmánuður means Sun Month and is the typically the brightest time in the north. Around June 21st is Summer Solstice. This was also the time of the Icelandic Althing, where people came in from all over to work out new contracts, figure out legal disputes, have marriages, and the like.

It was said that the solstice night was a time when elves and land-spirits would come out and dance around the fire with humans. Young women roll naked in the morning dew to get more fertile. This time was also believed to be good for divination, collecting of herbs, and doing seidhr or spaecraft.

Heyannir - July 13th - August 14th. Heyannir ("hay time") is the fourth summer month. It was the time for cutting and drying hay. In farming communities, a small celebration followed the harvest of hay.

Tvímánuður - August 15th - September 14th. Depending on the region, harvesting of hay continued into this month. But it was also a time of harvesting things like corn and grains. Once the work was done, a small celebration was made.

Haustmánuður - September 15th - October 13th. Haustmánuður is the “Autumn Month” and last month of summer. Around the 21st of September is the Autumnal Equinox. Rounding up of sheep, finishing the harvest of certain grains, making plans for winter, and the like were common.

Primary source:

High Days and Holidays in Iceland (1995) by Árni Björnsson - Translated to English in 1995. The Icelandic version is 1993.

Secondary sources:

Norse Months and Holidays (Youtube, 2020), Dr. Jackson Crawford

Blót according to the Icelandic tradition

The ordinances of the Ásatrúar are called blót. There are 4 main blót’s performed every year and is based upon the Old Norse calander. In addition to them, Landvættr blót is held simutaniously in all four quarters of Iceland on the sovereignty day (1st of December).

Þorrablót is always held on Bóndadaginn (Farmers day) and Goðar perform a blót in their provinince at least once a year.

Sigurblót

Sigurblót is held on the first day of summer (20th of April) and was sort of a independance day far back in time. The first day of summer is also the day the Icelandic Ásartrúarfélag was founded in the year 1972.

Vorblót is expecially honored to Freyr and freyja, the Vanir and the gods of life and fertility of the earth.

Þingblót

Þingblót is held during the summer solstice at Þingvellir by the Öxará, the Icelanders sacred place of assembly. Alþing usually esembled there around that time of the year in the olden times all the way up until 1798.

This blót is deticated to the laws, civilisation, the congress and the society. We also celibrate the amount of vegitation and the longest period of sunlight.

Veturnáttablót

Veturnáttablót is held on the first day of winter that always happens on a Saturday during the last week of October. This blót is deticated to the harvest of the fall and all the living creatures that dissapear into the neverending circle of life.

Jólablót

Jólablót during the winter solstice is the ancient festival of light when the sun begins to sit higher in the sky and the days begin to becom longer again. This is the turningpoint for new beginings, a new year, new life and is also the festival of the children who often do their part during a special light ceremony. There we blót for a good year to come, in honor of Frey, for a good year and peace.

Landvættablót

Landvættablót are heldin all 4 quarters of Iceland at Þingvellir on the 1st of December every year. The blót are deticated to the vættir that have since the time of settlement guarded the 4 quarters of Iceland, and have been controled by the Goðar at the same time in each region of the country.

The rock-giant blót is held in the southern region, the bull blót in the western region, the eagle blót in the northern region, the dragon blót is held in the eastern part of the country and unity blót is held at Lögberg, the nations cultural centerpoint of sorts.

Þorrablót

The Ásatræuarfélagsins Þorrablót is held every year on Bóndadagurinn (farmers day). There is served þorramatur ( traditoinal Icelandic food made in the same way since the viking age), entertainment and a welcome gathering for people during a season that often is hard on people.

Traditions

There are many customs and traditions that where and are practiced within Ásatrú.

Ausa vatni & Nafnfesta

The Viking baby had to endure many hardships since they were born. Ever since their first cry saying hello to the world, the adults would examine it for any physical disabilities. If yes, the children would be abandoned into the forest and left there to die. But once they passed the test, they could join the naming ritual which took place once in a lifetime.

When the mother managed to deliver her baby, the baby would be placed on the ground. The father would come there and pick up the baby. This presented the fact that the father accepted the child to be his offspring.

It was the father who examined the child whether he had any physical problems or disabilities. And he had to judge whether the child he was holding had a future or not. This process decided the fate of the child: whether to live with their parents or to be abandoned in society.

If nothing wrong happened to the child, they would endure the ritual Ausa Vatni. This ritual was carried out by sprinkling the water over the baby and gave him/her a name.

The ceremony was an ancient and formal ritual dating back to the Old Norse time. To leave the child in the jungle till death was considered to be murder after the formal ceremony. Northern Frankish tribes practised this ritual in their daily lives. The scholars believed that the baptism of the Christians somewhat resembled the Ausa Vatni of the Vikings.

And a gift was also given to the child whether the family was rich or not. It was called the Nafnfest which meant the Name Fastening.

The parents, especially the fathers, would give their newly-born child a gift, for example, a ring, weapons, or other tokens. Those gifts were commonly related to the farms or the lands.

Glíma

I’m bored of lying here in an ugly cave;

it’s better at home in Helgafell

where they have dancing and wrestling.

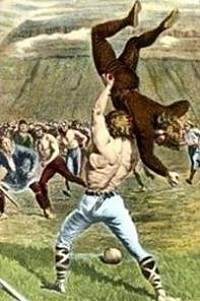

Glíma has been a part of the life of Icelanders from the original settlement of the land until today, and it evolved in parallel with the multitude of changes that Icelandic society has undergone. Based on the folkloric poem above, spoken by a dead man in his grave, glíma even followed Icelanders between one world and the next.

For the most part, glíma has an unbroken history from Iceland’s earliest days through to the present day. From the original settlement of the land to the loss of independence to the changes of ruling kingdom; through natural disasters, pandemics and mass emigrations; from heathenism to the conversion to the reformation; through all these changes, glíma has stood by the side of Icelanders and refused to move an inch when the situation turned hard, much like a loyal dog.

In reality glíma is the only sport that survived the Viking Age. Glíma was to Icelanders a tool of survival in the days when the very real threat of a violence lay around each corner. Later, glíma became a pedagogical tool for training youth when the violence of the earlier era diminished. Glíma was one of the most powerful weapons in the battle for Iceland’s independence as Icelanders began that struggle. And in the recent decades, glíma has been a noble, as well as an unconventional sport for the public to participate in.

The purpose of glíma has changed through the ages, and accordingly, the methodology for glíma has changed as well. All these changes can be followed, because glíma has a nearly unbroken history from the beginning of Iceland’s settlement. The glíma of old was like a Swiss-army knife: one tool with many purposes. Glíma was an activity of entertainment wherever people congregated. Glíma was one of the surest ways to prove oneself and one’s worth to others. Glíma was a practical method for keeping oneself warm during winter travels in the frigid Icelandic climate. Glíma was a brutal weapon and tool of survival in a dangerous world.

Glíma was used to take down giants, ghosts, zombies, outlaws, armed enemies and many other evil-doers. Even empires were taken down a notch using glíma during Iceland’s march to independence.

A grand turning point in the life of Icelanders as well as in glíma occurred when the monumental idea of national independence sprang into the national consciousness during the middle of the 19th century. It was a period of great turmoil, when Icelanders had to make decisions about what it was to be Icelandic: what elements were Icelandic, and what elements were not Icelandic. Glíma became a tool for separation and distinctiveness. Glíma became something that could be called uniquely Icelandic: the sword and the shield of a new nation.

It was then that we see for the first time the glíma we know today: the modernized glíma. This new and spectacular future of glíma seems to have originated at the school at Bessastaðir, which was the center of education in Iceland at this time. Students practiced glíma each day in the lobby of the Bessastaðir school. These students later were the people who most enthusiastically agitated for and guided the move to Icelandic independence. Today Bessastaðir is the official residence of the president of Iceland.

Only recently has it become clear the degree to which these changes in glíma during this period empowered Icelanders.

When Iceland declared independence on June 17, 1944, glíma was practiced both in Iceland and abroad, wherever Icelanders celebrated their independence. Glíma had been a catalyst for Iceland becoming a free and independent nation.

After independence, glíma continued to evolve. Its purpose changed again, since it was not needed as a tool of separation and uniqueness to the same degree.

Today, glíma is an organized sport with its own union inside the national Olympic and sports association of Iceland, just like other sports. Men and women of all ages participate and compete in glíma using a formal set of rules, and with formal training available.

Glíma will always be more than merely a competitive sport. Glíma has stood next to Icelanders from settlement through today, maintaining Iceland’s ancient legacy. Despite the changes through the centuries, the spirit of the settlement-era glíma still holds strong in modern glíma. Many of the throws are the same and bear the same names as in the ancient sources. The modern glíma-belt encourages a very similar methodology of delivering the throws as is depicted in the ancient sources. A clear example is the hábrögð (high tricks) where one’s partner is raised to the chest of the thrower and then thrown down.

Ancient glíma is in evidence in the placenames of multiple locations around Iceland: Fangbrekka (wrestling hills) in Þingvellir, Glímustofu (Glíma-hall) in Dritvík; and Hryggbrjóti (back-breaker) in Hringsdalur. Throughout the world, Hryggbrjótur remains the only known glíma-stone, used in ancient times to break the back of one’s opponent.

Echoes of glíma remain as phrases in the everyday speech of Icelanders, with sayings such as: að ná undirtökunum (to have the undergrip in wrestling, which means to have the upper hand in a dispute); að láta kné fylgja kviði (to let the knee follow the lower abdomen, a controlling position on the ground, which means to follow through fully); and many others.

Today glíma is more than a tool of survival, more than a pedagogical tool, more than a tool of separation and uniqueness, more than a sport, and more than a method of wrestling. Glíma is the culture, history, and mentality of Icelanders in a moving art form. Glíma rightly holds the title of the National Sport of Iceland.